American Delegation of Savoy Orders

Umberto II: His Life as Crown Prince, Lieutenant General of the Realm and King

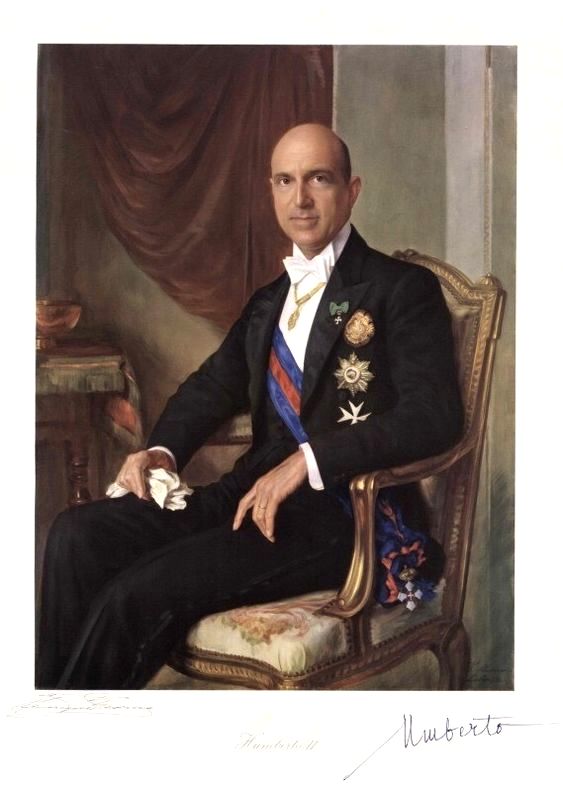

KING UMBERTO II OF ITALY

Second in American Delegation of Savoy Orders’ History Lecture Series

Summary by our Editor, Uff. John Shannon

Second in American Delegation of Savoy Orders’ History Lecture Series

Summary by our Editor, Uff. John Shannon

In honor of the centenary of his birth, September 1904, the late King Umberto II, last King of Italy, was the subject of a in-depth lecture prepared by Cav. Gr. Cr. Nobile Francesco Carlo Griccioli, a scholar, writer and lecturer on European military history and the current Delegate of Tuscany to the Dynastic Orders of the Royal House of Savoy, and delivered at and by the Director of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, Cav. William P. Johns, on Monday 18 October 2004. This was the second in the American Delegation of Savoy Orders’ History Lecture Series.

Umberto was the son of Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy, who became King in 1900 and abdicated in May 1946, in favor of HRH Crown Prince Umberto. It was, of course, during his long reign that Fascism manifested itself as Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, rose to political power. And it was Mussolini who led Italy into chimerical colonial adventures and into an ill-fated alliance with Nazi Germany.

Vittorio Emanuele has long been suspected by scholars of, at best, passivity vis-à-vis Mussolini’s reckless leadership or, at worst, complicity with Il Duce. Mr. Griccioli’s lecture shed much light on the political circumstances of the time. In effect, things were not so simple. In Mr. Griccioli’s view, the King despised Mussolini; but he also believed that any attempt to remove him from power (the army was absolutely loyal to the Crown) would lead to civil war and possibly even to the collapse of the monarchy.

When Italy entered into the Second World War, the King wrote a memo to his son, Crown Prince Umberto (whom Mussolini had “demoted” from Crown Prince, with its hereditary implications, to simply Prince of Piedmont), analyzing the situation. The King outlined three options: arrest Mussolini and take control of the government himself; abdicate; or go along and try to make the best of a bad situation.

Vittorio Emanuele anticipated that Italy and its German ally would lose the war. If he seized power, he believed it would trigger a constitutional crisis leading to civil war; and the monarchy might be overthrown. If he abdicated, that would be playing into Mussolini’s hands. (Mussolini resented the King as a brake on his authority.) But if he remained, Vittorio Emanuele would be in a position to maintain a kind of stability: there would be at least one person in the state Mussolini would have to pretend to respect. But the King would do as little as possible to endorse Mussolini. He seldom appeared with him and, indeed, made few public appearances at all Prince Umberto was a dutiful son. In the Italian context, he was thought of as a liberal, and was no admirer of Mussolini. He and Princess Maria José, daughter of the universally admired World War I hero, King Albert I of Belgians and Queen Elisabeth, lived away from Rome in Naples, again to avoid appearances with Il Duce. They were a popular and attractive couple and did much to help the royal family’s public image by visiting hospitals and undertaking goodwill trips around the country and the world.

The Prince’s finest hour came when his father named him Lieutenant General of the Realm in June 1944 before leaving the country for Egypt. In May 1946, Vittorio Emanuele abdicated and Umberto became King. By then, it was decided that there would be a plebiscite on what form of government Italy would adopt: constitutional monarchy or republic. The vote would be in June 1946. Umberto did his best, and was much admired for his efforts to act as a model sovereign during the months leading up to the referendum. Winston Churchill, who met Umberto, praised him as by far the most intelligent and competent political figure in Italy at the time.

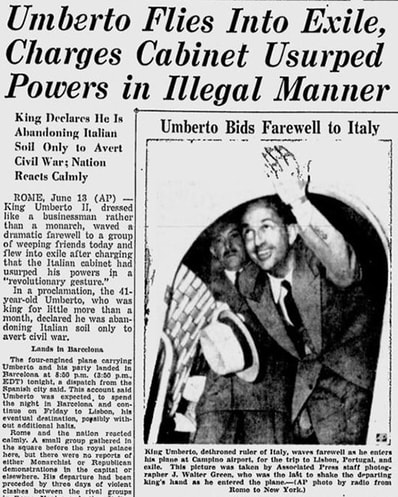

When the votes were counted, it was found that there was a slim majority in favor of establishing a republic. (Curiously, however, while the abolition of the monarchy was proclaimed, the establishment of the republic was not.) There were many irregularities in the voting and the operation is generally thought not have been conducted in a strictly correct fashion.

The King could have challenged the results but that, again, might have triggered a civil war and he had no wish to cause his defeated country any more agony. He chose to abide by the results and went to live in Portugal. He never formally abdicated the throne and remained King during his exile.

Umberto was the son of Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy, who became King in 1900 and abdicated in May 1946, in favor of HRH Crown Prince Umberto. It was, of course, during his long reign that Fascism manifested itself as Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, rose to political power. And it was Mussolini who led Italy into chimerical colonial adventures and into an ill-fated alliance with Nazi Germany.

Vittorio Emanuele has long been suspected by scholars of, at best, passivity vis-à-vis Mussolini’s reckless leadership or, at worst, complicity with Il Duce. Mr. Griccioli’s lecture shed much light on the political circumstances of the time. In effect, things were not so simple. In Mr. Griccioli’s view, the King despised Mussolini; but he also believed that any attempt to remove him from power (the army was absolutely loyal to the Crown) would lead to civil war and possibly even to the collapse of the monarchy.

When Italy entered into the Second World War, the King wrote a memo to his son, Crown Prince Umberto (whom Mussolini had “demoted” from Crown Prince, with its hereditary implications, to simply Prince of Piedmont), analyzing the situation. The King outlined three options: arrest Mussolini and take control of the government himself; abdicate; or go along and try to make the best of a bad situation.

Vittorio Emanuele anticipated that Italy and its German ally would lose the war. If he seized power, he believed it would trigger a constitutional crisis leading to civil war; and the monarchy might be overthrown. If he abdicated, that would be playing into Mussolini’s hands. (Mussolini resented the King as a brake on his authority.) But if he remained, Vittorio Emanuele would be in a position to maintain a kind of stability: there would be at least one person in the state Mussolini would have to pretend to respect. But the King would do as little as possible to endorse Mussolini. He seldom appeared with him and, indeed, made few public appearances at all Prince Umberto was a dutiful son. In the Italian context, he was thought of as a liberal, and was no admirer of Mussolini. He and Princess Maria José, daughter of the universally admired World War I hero, King Albert I of Belgians and Queen Elisabeth, lived away from Rome in Naples, again to avoid appearances with Il Duce. They were a popular and attractive couple and did much to help the royal family’s public image by visiting hospitals and undertaking goodwill trips around the country and the world.

The Prince’s finest hour came when his father named him Lieutenant General of the Realm in June 1944 before leaving the country for Egypt. In May 1946, Vittorio Emanuele abdicated and Umberto became King. By then, it was decided that there would be a plebiscite on what form of government Italy would adopt: constitutional monarchy or republic. The vote would be in June 1946. Umberto did his best, and was much admired for his efforts to act as a model sovereign during the months leading up to the referendum. Winston Churchill, who met Umberto, praised him as by far the most intelligent and competent political figure in Italy at the time.

When the votes were counted, it was found that there was a slim majority in favor of establishing a republic. (Curiously, however, while the abolition of the monarchy was proclaimed, the establishment of the republic was not.) There were many irregularities in the voting and the operation is generally thought not have been conducted in a strictly correct fashion.

The King could have challenged the results but that, again, might have triggered a civil war and he had no wish to cause his defeated country any more agony. He chose to abide by the results and went to live in Portugal. He never formally abdicated the throne and remained King during his exile.

Message of HRH Prince Victor Emmanuel,

Duke of Savoy, Prince of Naples,

On the Occasion of the Centennial Anniversary

of the Birth of H. M. King Umberto II

and of His Visits to New York in 1963 and 1967

It was with great pleasure that I learned of the history lecture commemorating the centennial of the birth of my august father, King Umberto II, and of his visits to New York. I cannot forget the account he gave me, on his return, of that second visit that took place on 13 to 15 March, 1967. It is a memory that I cherish both with joy and sadness: joy because he was received as a head of state, and sadness because I read in his eyes a deep sense of sorrow.

Liberty is a fundamental cornerstone of life in the United States; I cannot, therefore, but recall the heartfelt anguish of exile enforced upon my father and endured by him with Christian fortitude and resignation for almost four decades.

Towards the end of his life on this earth, even greater pain was added when a final wish was denied; namely that he be allowed to see his beloved fatherland one last time. this is further reason that recalling the significance and joy of the New York visits gives me now such particular pleasure.

With this in mind, I wish to congratulate the American Delegation of Savoy Orders – one of the most active. felicitations are due to the American Delegate, Cav. Gr. Cr. Avv. Carl Morelli and to Cav. Gr. Cr. Francesco Griccioli for his contribution. I extend further thanks to Cav. Marco Grassi, to Gr. Uff. Baron Mario di Genova di Salle and to Cav. William Johns for their enthusiastic participation.

It is my sincere hope that, in the near future, accompanied by my wife and our son, H.R.H. Prince Emanuele Filiberto, I shall be able to visit your magnificent city again. the tragic events of three years ago have greatly saddened us, yet, our firmly held religious beliefs lead us to pray to the lord for a future when peace and justice will prevail.

Victor Emmanuel

Duke of Savoy, Prince of Naples,

On the Occasion of the Centennial Anniversary

of the Birth of H. M. King Umberto II

and of His Visits to New York in 1963 and 1967

It was with great pleasure that I learned of the history lecture commemorating the centennial of the birth of my august father, King Umberto II, and of his visits to New York. I cannot forget the account he gave me, on his return, of that second visit that took place on 13 to 15 March, 1967. It is a memory that I cherish both with joy and sadness: joy because he was received as a head of state, and sadness because I read in his eyes a deep sense of sorrow.

Liberty is a fundamental cornerstone of life in the United States; I cannot, therefore, but recall the heartfelt anguish of exile enforced upon my father and endured by him with Christian fortitude and resignation for almost four decades.

Towards the end of his life on this earth, even greater pain was added when a final wish was denied; namely that he be allowed to see his beloved fatherland one last time. this is further reason that recalling the significance and joy of the New York visits gives me now such particular pleasure.

With this in mind, I wish to congratulate the American Delegation of Savoy Orders – one of the most active. felicitations are due to the American Delegate, Cav. Gr. Cr. Avv. Carl Morelli and to Cav. Gr. Cr. Francesco Griccioli for his contribution. I extend further thanks to Cav. Marco Grassi, to Gr. Uff. Baron Mario di Genova di Salle and to Cav. William Johns for their enthusiastic participation.

It is my sincere hope that, in the near future, accompanied by my wife and our son, H.R.H. Prince Emanuele Filiberto, I shall be able to visit your magnificent city again. the tragic events of three years ago have greatly saddened us, yet, our firmly held religious beliefs lead us to pray to the lord for a future when peace and justice will prevail.

Victor Emmanuel

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS OF CARL J. MORELLI, PRESIDENT

OF THE AMERICAN FOUNDATION OF SAVOY ORDERS, INC.

Good evening. My name is Carl Morelli and I'm President of the American Foundation of Savoy Orders. I'm also the Delegate of his Royal Highness Prince Victor Emmanuel of Savoy for the dynastic orders of the Italian Royal Family in the United States and Canada.

I greet you tonight not just on my own behalf and on behalf of his Royal Highness, but also on behalf of the Board of Directors of the Savoy Foundation, some of whom are here this evening. And, I also welcome a very special guest, one of our dear confreres in the Savoy Order who is here this evening, his Excellency Grand Cross Archbishop Celestino Migliore, Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations.

This is the second lecture in our series on the history of the Royal House of Savoy. Those of you who attended the first lecture last year remember Bill Warren's enlightening treatment of the life of Prince Eugene of Savoy, a celebrated general, statesman and bibliophile of late 17th and early 18th century Europe. This evening we also have chosen a very exciting topic to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of the subject of our lecture, His Majesty King Umberto II, the last King of Italy.

Because so little is known in this country about the history of the Royal House of Savoy we thought that it was time to do something about it. If you ask the average American what the name Savoy means to him, he might say, well, isn't there a cabbage called Savoy cabbage? That's absolutely right, there is. Isn't there a theatre in London, the Savoy Theatre? Yes. And those of you who are devotees of the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas know that quite well. In fact, you're called Savoyards, although in Italian the devotees of the Italian Royal Family are known as Savoiardi. And, students of the jazz age in the United States will remember the legendary Savoy nightclub as well as the famous jazz tune, Stomping at the Savoy, so popular in the 1930's. In the business world there's a Savoy hotel chain. There's a medical supply company on Long Island. A restaurant in Manhattan. There's even an English language magazine called Savoy for black Americans, presumably deriving its name from the famous Harlem nightclub.

With so many references to the name Savoy, it is not surprising that an education gap exists about the history of the Royal House of Savoy in this country. As a history major myself in college, I speak from experience that very little was taught about Italian history and almost nothing about the Italian Royal Family. Conversely, the Savoy Family is certainly very well known in Europe, having been sovereign for almost a thousand years since the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II, around the year 1003, conferred feudal rights to the lands of what is now the French province of Savoie, or Savoy, which was the old Roman province of Sabaudia, upon the first member of the Savoy Royal Family, Umberto Biancomano (the Whitehanded). In an unbroken line of sovereigns, the Savoy Royal Family reigned as sovereigns of that area until they ceded it to France under Napoleon III in 1860 in exchange for Lombardy. And then, of course, came the Savoy Family's historic role in the unification of Italy between 1860 and 1870.

And so, I'd like to thank the Board of Directors of the Foundation, including James Risk our Chairman, Robert La Rocca, who is here tonight, our Vice President, Richard Cosnotti, our Treasurer, David Skoblow, who is also here this evening, John Dunlap and Frank Giordano for their foresight and their vision in making this series of lectures a reality. We have incorporated this lecture series under the umbrella of the Savoy Foundation which primarily does charity works for poverty, medical causes and disaster relief. In fact, we are in the process of funding an ambulance for St. Vincent's Hospital as part of the charitable works of the Savoy Orders here in the United States. But, the American Delegation of Savoy Orders is only one Delegation of the 33 Delegations worldwide, all of whom are attempting to achieve humanitarian goals in today's world by incorporating the ancient charitable traditions of the Chivalric Orders of the House of Savoy.

I am also very grateful to the Grand Master of the Savoy Orders, His Royal Highness Prince Victor Emmanuel of Savoy, whose very poignant and beautifully written message is in the program on your seat when you arrived this evening. His encouragement and support of our Delegation and our Foundation is the catalyst that allows us to carry on the charitable and educational work we do today. The Prince is sorry he cannot be here this evening, but hopes to come to the USA in the very near future. We will certainly keep everyone advised when he does.

Before I make introductions tonight, I ask that you kindly turn off your laptops, your cell phones, your microwave ovens, and all other electronic devices that might interrupt our speaker. He has wonderful focus, but we don't want to break his concentration if we can avoid it.

I could not possibly introduce the next individuals until I thanked them all first: so, thank you to our Savoy Lecture Series Chairman, Marco Grassi for his wonderful work in assembling this lecture series, to our dear friend Francesco Carlo Griccioli who could not be with us this evening, but who wrote the lecture, to our confrere William Johns who is going to be reading Francesco's lecture and who has also invited us to use this wonderful venue, the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, a truly legendary establishment. We thank him from the bottom of our hearts for that. And, in addition, we want to thank Luke Pontifell, one of our confreres, who printed those beautiful invitations. He certainly enhanced this evening's lecture with his production of the elegant invitations. So, now let me introduce our Chairman of the Savoy History Lecture Series, Marco Grassi. I, for one, will listen with great attention to this lecture tonight, which I'm sure will be fascinating for everyone.

Thank you.

OF THE AMERICAN FOUNDATION OF SAVOY ORDERS, INC.

Good evening. My name is Carl Morelli and I'm President of the American Foundation of Savoy Orders. I'm also the Delegate of his Royal Highness Prince Victor Emmanuel of Savoy for the dynastic orders of the Italian Royal Family in the United States and Canada.

I greet you tonight not just on my own behalf and on behalf of his Royal Highness, but also on behalf of the Board of Directors of the Savoy Foundation, some of whom are here this evening. And, I also welcome a very special guest, one of our dear confreres in the Savoy Order who is here this evening, his Excellency Grand Cross Archbishop Celestino Migliore, Permanent Observer of the Holy See to the United Nations.

This is the second lecture in our series on the history of the Royal House of Savoy. Those of you who attended the first lecture last year remember Bill Warren's enlightening treatment of the life of Prince Eugene of Savoy, a celebrated general, statesman and bibliophile of late 17th and early 18th century Europe. This evening we also have chosen a very exciting topic to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of the subject of our lecture, His Majesty King Umberto II, the last King of Italy.

Because so little is known in this country about the history of the Royal House of Savoy we thought that it was time to do something about it. If you ask the average American what the name Savoy means to him, he might say, well, isn't there a cabbage called Savoy cabbage? That's absolutely right, there is. Isn't there a theatre in London, the Savoy Theatre? Yes. And those of you who are devotees of the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas know that quite well. In fact, you're called Savoyards, although in Italian the devotees of the Italian Royal Family are known as Savoiardi. And, students of the jazz age in the United States will remember the legendary Savoy nightclub as well as the famous jazz tune, Stomping at the Savoy, so popular in the 1930's. In the business world there's a Savoy hotel chain. There's a medical supply company on Long Island. A restaurant in Manhattan. There's even an English language magazine called Savoy for black Americans, presumably deriving its name from the famous Harlem nightclub.

With so many references to the name Savoy, it is not surprising that an education gap exists about the history of the Royal House of Savoy in this country. As a history major myself in college, I speak from experience that very little was taught about Italian history and almost nothing about the Italian Royal Family. Conversely, the Savoy Family is certainly very well known in Europe, having been sovereign for almost a thousand years since the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II, around the year 1003, conferred feudal rights to the lands of what is now the French province of Savoie, or Savoy, which was the old Roman province of Sabaudia, upon the first member of the Savoy Royal Family, Umberto Biancomano (the Whitehanded). In an unbroken line of sovereigns, the Savoy Royal Family reigned as sovereigns of that area until they ceded it to France under Napoleon III in 1860 in exchange for Lombardy. And then, of course, came the Savoy Family's historic role in the unification of Italy between 1860 and 1870.

And so, I'd like to thank the Board of Directors of the Foundation, including James Risk our Chairman, Robert La Rocca, who is here tonight, our Vice President, Richard Cosnotti, our Treasurer, David Skoblow, who is also here this evening, John Dunlap and Frank Giordano for their foresight and their vision in making this series of lectures a reality. We have incorporated this lecture series under the umbrella of the Savoy Foundation which primarily does charity works for poverty, medical causes and disaster relief. In fact, we are in the process of funding an ambulance for St. Vincent's Hospital as part of the charitable works of the Savoy Orders here in the United States. But, the American Delegation of Savoy Orders is only one Delegation of the 33 Delegations worldwide, all of whom are attempting to achieve humanitarian goals in today's world by incorporating the ancient charitable traditions of the Chivalric Orders of the House of Savoy.

I am also very grateful to the Grand Master of the Savoy Orders, His Royal Highness Prince Victor Emmanuel of Savoy, whose very poignant and beautifully written message is in the program on your seat when you arrived this evening. His encouragement and support of our Delegation and our Foundation is the catalyst that allows us to carry on the charitable and educational work we do today. The Prince is sorry he cannot be here this evening, but hopes to come to the USA in the very near future. We will certainly keep everyone advised when he does.

Before I make introductions tonight, I ask that you kindly turn off your laptops, your cell phones, your microwave ovens, and all other electronic devices that might interrupt our speaker. He has wonderful focus, but we don't want to break his concentration if we can avoid it.

I could not possibly introduce the next individuals until I thanked them all first: so, thank you to our Savoy Lecture Series Chairman, Marco Grassi for his wonderful work in assembling this lecture series, to our dear friend Francesco Carlo Griccioli who could not be with us this evening, but who wrote the lecture, to our confrere William Johns who is going to be reading Francesco's lecture and who has also invited us to use this wonderful venue, the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, a truly legendary establishment. We thank him from the bottom of our hearts for that. And, in addition, we want to thank Luke Pontifell, one of our confreres, who printed those beautiful invitations. He certainly enhanced this evening's lecture with his production of the elegant invitations. So, now let me introduce our Chairman of the Savoy History Lecture Series, Marco Grassi. I, for one, will listen with great attention to this lecture tonight, which I'm sure will be fascinating for everyone.

Thank you.

UMBERTO II:

His Life as Crown Prince, Lieutenant General of the Realm and King

By

Cav. Gr. Cr. Francesco Carlo Griccioli

Delivered by

Cav. William P. Johns

October 18, 2004, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society

|

This year marks the centenary of the birth of Umberto, Crown Prince of the Royal House of Savoy, who, at least to this day, was to be the last King of united Italy. It is an anniversary to be remembered: it celebrates a Prince, great in his misfortune, yet a statesman who always placed the interests of his country above those of his Dynasty. In this he was very consistent with the centuries-long traditions upheld by the Princes of the House of Savoy. Although he left Italy voluntarily in June 1946 after a national referendum, he was, nonetheless, condemned a year later to an unjust exile. Despite this, Umberto II never abdicated the throne and remained King in spirit and dignity, but also, and more importantly, monarch de jure, until his death in Geneva on the 18th of March, 1983. In all those years, Italy, so near and yet so far, remained constantly in his thoughts and in his heart until he drew his last breath.

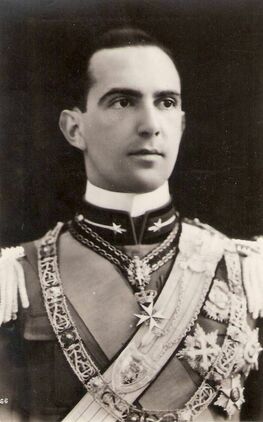

Umberto of Savoy was born in the castle of Racconigi, near Turin, on September 15, 1904. He was the only son - he had four sisters - of Victor Emanuel III, third King of Italy, and Queen Elena, born Princess of Montenegro. Italy’s Prime Minister, Giovanni Giolitti, acting in his role as “Notary to the Crown” signed the birth certificate and although the happy event was greeted with great popular rejoicing, it also coincided with waves of widespread strikes and socialist agitation. His baptism took place in December of that year in the presence of Prince Albert of Prussia and the Duke of Connaught, representing the official godfathers; the Emperor William II of Germany and King Edward VII of England. |

|

|

Very much in the tradition of the House of Savoy and, for that matter, most other royal households of the time, Prince Umberto was the product of a very strict upbringing. As the only male offspring, he was Heir to the Throne; his education, therefore, had to conform not only to the ancient military traditions of his House but also to the prospect of his becoming the constitutional sovereign of a state, now counted among Europe’s major powers.

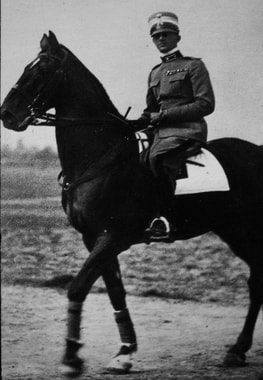

Several tutors schooled the young Prince until, at age nine, he was consigned to the supervision of a stern but benevolent Royal Navy officer, Attilio Bonaldi. Admiral Bonaldi, who had been one of Italy’s first submarine commanders, arranged the Prince’s days in a succession of classes covering a wide variety of subjects and taught by a hand-picked cadre of teachers. Over the years, other activities included sports, mountain climbing and a cruise on the Royal Navy cruiser Puglia. An aspect of the Prince’s personality became evident from his earliest childhood and remained constant throughout his life: it was his fervent and very genuine religious devotion. It has been noted that the intensity of this sentiment may, in part have derived from his mother who, as a Princess of Montenegro, was raised in the traditions of the Eastern Orthodox Church. At age fourteen, Prince Umberto was enrolled in the Rome Military College where he studied for three years. This was followed by a year at the Military Academy in Modena, whereupon, in 1922, the Prince received his commission as Second Lieutenant in the First Sardinian Grenadiers Regiment. Upon his 21st birthday, in 1925, the Prince was promoted to First Lieutenant and attached to the 91st Infantry Regiment, headquartered in Turin. He was universally described in these years as an excellent officer, respectful of higher authority and much loved by his subordinates. |

|

In 1922, Benito Mussolini, in the wake of several years of violent post-war social unrest, was named Prime Minister. His party, the Fascists, had no significant representation in Parliament, but it gave to the new Prime Minister by almost all the democratically elected parties an overwhelming vote of confidence. He promised to reestablish order to the torn social fabric and prosperity to the ravaged economy. It was the Government’s early successes and strong popular support that induced the Crown to accede to a series of laws promulgated in 1926 that severely curtailed the personal freedoms, heretofore guaranteed by Italy’s constitution since unification in 1865. These included restrictions on the press, political parties and public assemblies. The King, Victor Emanuel III, perfectly well understood that the only way to block the Fascist ascendancy – of which he was profoundly suspicious – would have been to sponsor a coup d’ètat by the military, unquestionably loyal to the Crown. This, of course, would have sparked a crisis with unimaginable consequences, and the King, rigorously schooled to respect the State and its statutes, was quite incapable of such a drastic step. It was also during these years that the Prince’s uneasy relationship with the emerging Fascist regime began. The mutual mistrust between the King and Mussolini also continued to grow, and, as a consequence, the distance between Mussolini and the Crown Prince. Not surprisingly, the activities of the entire Royal Family were very closely watched by Mussolini. The Prince was regarded as a potential threat, given his very well-known liberal intellectual and cultural leanings. The Senior Aide de Camp of the Prince’s Household, General Ambrogio Clerici, had the often difficult task of acting as a diplomatic buffer. The undeniable popular support that the Government enjoyed, particularly in this early phase of its twenty-year tenure, made his task particularly difficult.

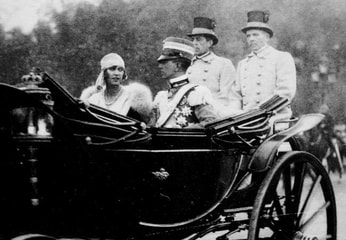

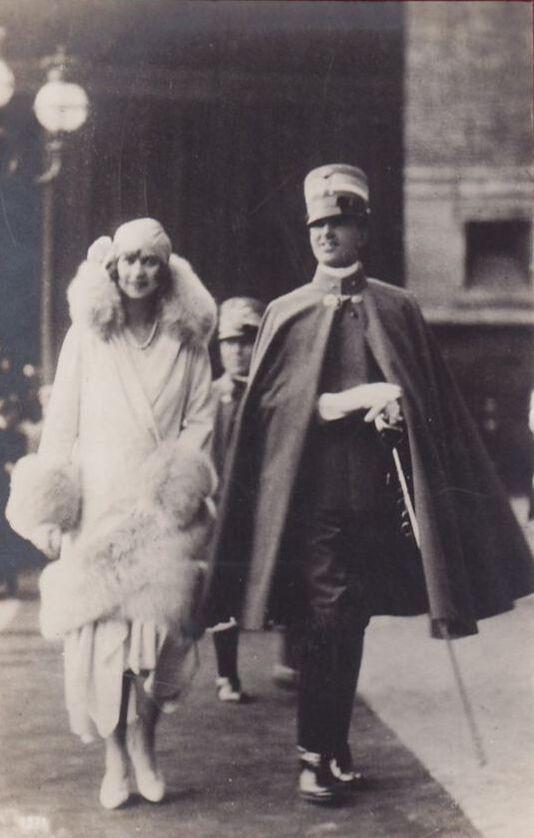

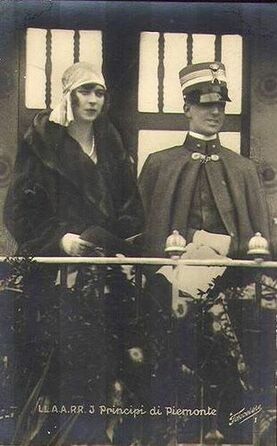

A further step in this confrontation was taken by the Government when, in 1928, with the approval of Parliament, it enacted a law that gave it certain prerogatives limiting the Royal House on a matter very close to its interests: the eventual succession of the Monarch. As a result of this decree, Prince Umberto’s official title was changed from ‘Crown Prince’ to ‘Prince of Piedmont’ – a very significant difference that, in effect, sanctioned the Government’s control over the succession and the Heir’s ascent to the Throne. During the patriotic and nationalistic delirium that took hold of the country during the Ethiopian Campaign of 1935-6, Mussolini showed his disdain of the Royal Family by rigorously denying Prince Umberto a command in the field and focusing all official dispatches on the Government’s pre-eminent role in the ‘victories’ abroad. The rift between Monarchy and Government was, by now, irreconcilable. It was during the years of the First World War, when he was still a youngster, that the Prince first met the woman that would become his wife. Princess Maria Josè, daughter of the King and Queen of Belgium, was accompanying her parents on a visit to Italy and the Italian front lines. The couple remained friends and married in 1930. The event was occasion for great popular festivities and was marked by a general outpouring of sincere affection for the strikingly handsome and elegant Prince and his beautiful, truly regal, bride. They cut a remarkable figure – surely the most photogenic and widely admired young couple of their generation. But in a political and more significant sense, the arrival in Italy of the Belgian Princess could not fail to enhance the liberal profile of the Crown Prince. Having been reared in a Royal Family rigorously observant of the democratic traditions of the Belgian State, Maria Josè was, also by nature a free and independent spirit. She, even more than the Crown Prince, made no secret of her profound aversion to the progressive erosion of those same democratic traditions in her adoptive country. |

King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy with Grandson, the Prince of Naples who became the Crown Prince in May 1946

King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy with Grandson, the Prince of Naples who became the Crown Prince in May 1946

1937 was marked, for the Royal Family, by the joyous event of the birth of a boy. He was given the name of Vittorio Emanuele, that of the King, his paternal grandfather and of Victor Emanuel II, the first King of united Italy. Despite the 101-gun salutes and celebrations, however, the event did little to change the purely ceremonial and marginal position to which the Princes of Piedmont, Umberto and Maria Josè, had been relegated.

The worst offense to the Sovereign and the Crown Prince was yet in store: in 1938 the Government issued a proclamation promoting Mussolini to the rank of “First Marshal of the Empire” – a totally unprecedented title that placed the Fascist leader on a military par with the King! A stiff protest was immediately forthcoming from the Royal Palace to this affront: the King made it clear that, had it not been for the international crisis that was rapidly bringing Europe to the brink of war, he would surely have abdicated. Although he undoubtedly considered taking this fatal step, he also knew that doing so, would have left his nation totally in the thrall of an all-powerful and, at that point, all-popular, Duce. With his intimates, Mussolini was very clear. To his Foreign Minister and son-in-law Count Galeazzo Ciano, he confided: “At the next opportunity we will go still further in the assumption of power…this will be when the authoritative signature of the King will be replaced with that one, less so, of the Prince”. There is absolutely no doubt that, had the King died at any point during this period, Mussolini would have moved quickly and decisively to terminate the monarchy.

The situation was not helped, that same year, during Hitler’s state visit to Italy: the Royal Family’s antipathy to the Teutonic warlord was all too clear, as was Mussolini’s impatience with the monarchy. In particular, the Prince and Princess of Piedmont never left their residence in Naples and only appeared there in public on ceremonial occasions. The Prince purposely kept himself at a distance from all government initiatives, particularly the more odious ones such as the annexation of Albania, the elevation of the fascist party to a constitutional state instrument, and the so-called ‘racial laws’. His father, the King’s, feelings at this time regarding the latter of these iniquitous initiatives is the following exchange that occurred between Mussolini and King Victor Emanuel III during one of the weekly briefings of the Prime Minister to the sovereign:

Mussolini: “Your Majesty, there are some 20.000 Italians, weakly constructed, who are moved to pity for what is happening to the Jews”.

The King: “Among those weakly constructed Italians you can include me as well”.

Mussolini: (quite taken aback and not knowing what to reply):”Certainly, your Majesty, these feelings deeply honor your Majesty”.

Crown Prince Umberto with his Son, Vittorio Emanuele

Crown Prince Umberto with his Son, Vittorio Emanuele

Although he signed the decrees, the King understood that, inevitably, they would lead to disaster. Just as clearly, he knew that opposing ‘Il Duce’ with the one element totally obedient to the Crown - the army - would precipitate a constitutional crisis and, worse, a civil war. It should be remembered that by this time the Fascist Party maintained its own, well- equipped and totally indoctrinated militia.

The question has often been asked: why did the Crown Prince not intervene more energetically with the King on these vital issues? Apart from the government’s constant efforts to relegate the Crown Prince to a marginal role, he himself was guided by the deeply ingrained family tradition that “the Savoia rule only one at a time”…in other words, a sharing of power between the father and the son would have been unthinkable; the Prince’s strict military upbringing was surely also a factor.

A capital and very illuminating insight into the monarchy’s predicament at the outbreak of war in 1940 is a memorandum of the King to the Crown Prince that, fortunately, has survived. With crystal-clear perception Victor Emanuel enumerates three options open to the monarch – each leading to equally fatal results:

Option One - The King refuses to go to war and deposes Mussolini who, nonetheless, remains in charge and has the King arrested. The King appeals to the Army: civil war ensues. Hitler intervenes, the King is executed and the two dictators pursue the war which, inevitably ends in defeat. After the war, memory of the fallen King will be revered and the monarchy possibly restored, but will not the victims of the civil war be seen as representing too high and unjustified a price for such a result?

Option Two – The King accepts going to war not willing to risk a civil conflagration. He then abdicates and flees into exile. Mussolini and Hitler continue the war eventually losing it. The Allies occupy Italy and restore the King to the Throne. Italians, however, for better or for worse will have fought Mussolini’s war: what respect will the reinstated monarch command upon his return – return from a comfortable exile immune from the sacrifices of war?

Option Three – Hitler and Mussolini win the war at the end of which the King will surely be ousted. But this third possibility is seen as infinitely remote: much more likely a defeat of the Axis after which not only the Italian people but the victors as well consider the King equally as responsible as the dictator for the debacle: both are eliminated.

If anything belies the stereotype of the old and befuddled King unwittingly a pawn of the tyrant Mussolini, it is this brilliantly lucid analysis that he shared with the Crown Prince. It proves, were all other evidence lacking, that Victor Emanuel clearly understood the dire implications of his actions…or better, his lack of actions. The fear of a civil war was ever uppermost in the King’s thoughts. The Prince would later inevitably become caught up with events as they unfolded. But, having been kept so long on the margins, he was ill-prepared to deal with the full weight of the political responsibility belatedly placed in his hands.

The question has often been asked: why did the Crown Prince not intervene more energetically with the King on these vital issues? Apart from the government’s constant efforts to relegate the Crown Prince to a marginal role, he himself was guided by the deeply ingrained family tradition that “the Savoia rule only one at a time”…in other words, a sharing of power between the father and the son would have been unthinkable; the Prince’s strict military upbringing was surely also a factor.

A capital and very illuminating insight into the monarchy’s predicament at the outbreak of war in 1940 is a memorandum of the King to the Crown Prince that, fortunately, has survived. With crystal-clear perception Victor Emanuel enumerates three options open to the monarch – each leading to equally fatal results:

Option One - The King refuses to go to war and deposes Mussolini who, nonetheless, remains in charge and has the King arrested. The King appeals to the Army: civil war ensues. Hitler intervenes, the King is executed and the two dictators pursue the war which, inevitably ends in defeat. After the war, memory of the fallen King will be revered and the monarchy possibly restored, but will not the victims of the civil war be seen as representing too high and unjustified a price for such a result?

Option Two – The King accepts going to war not willing to risk a civil conflagration. He then abdicates and flees into exile. Mussolini and Hitler continue the war eventually losing it. The Allies occupy Italy and restore the King to the Throne. Italians, however, for better or for worse will have fought Mussolini’s war: what respect will the reinstated monarch command upon his return – return from a comfortable exile immune from the sacrifices of war?

Option Three – Hitler and Mussolini win the war at the end of which the King will surely be ousted. But this third possibility is seen as infinitely remote: much more likely a defeat of the Axis after which not only the Italian people but the victors as well consider the King equally as responsible as the dictator for the debacle: both are eliminated.

If anything belies the stereotype of the old and befuddled King unwittingly a pawn of the tyrant Mussolini, it is this brilliantly lucid analysis that he shared with the Crown Prince. It proves, were all other evidence lacking, that Victor Emanuel clearly understood the dire implications of his actions…or better, his lack of actions. The fear of a civil war was ever uppermost in the King’s thoughts. The Prince would later inevitably become caught up with events as they unfolded. But, having been kept so long on the margins, he was ill-prepared to deal with the full weight of the political responsibility belatedly placed in his hands.

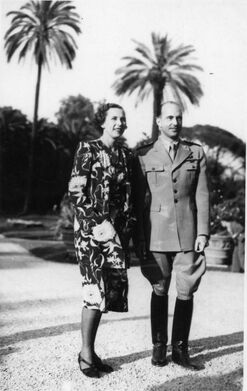

Crown Prince Humberto during Second World War

Crown Prince Humberto during Second World War

The Crown Prince’s subordinate status was even reflected in his military appointments. At the beginning of the war his duties were limited to being Inspector General on the French front. He then continued in this capacity on the home front, although he had always hoped and had aspired to be given a field command in Africa. In April 1942 the Prince was named Commander of Army Group South with the rank of Marshal of Italy, an essentially honorific title since effective command by that time was firmly in the hands of the German Field Marshal, Albert Kesselring.

As 1942 drew to a close, it was clear to every Italian staff and field commander that entering the war as allies of Nazi Germany had been a tragic miscalculation. Defeat of the Axis was only a matter of time and, on the home front, support for the fascist regime was rapidly evaporating. The Crown Prince was seen in many quarters, particularly the military, as the only alternative – the leader who had the moral authority to guide the nation out of the dreadful spiral of war. But such an initiative on the part of the Prince – effectively to subvert the authority of the King - would have been unthinkable. He had, after all, spent his entire adult life in the military – obedience to his superiors and obedience to the King had always guided his behavior.

The Prince was dutifully at his post in southern Italy as the climactic crisis of July 1943 began to unfold. It coincided with the first landing of Allied troops in eastern Sicily. By the 24th of July, Mussolini was persuaded to convene the highest consultative and political body of the state, the so-called Grand Council. It was composed of some 28 senior authorities of the fascist regime and had not met for more than four years. In the course of a stormy ten-hour session it voted, by an overwhelming majority, to request Mussolini to relinquish command of the Armed Forces, to call for the King to become again Supreme Commander and to resume his duties and responsibilities –– duties and responsibilities that had never been officially abolished and had been enshrined in the “Statuto”, the Kingdom’s Constitution, since 1848. The King, at last, had a juridical and constitutional opportunity to replace the government that had ruled Italy for over twenty years. He did so by naming a cabinet of non-political ‘technical’ ministers headed by Marshal Pietro Badoglio as Prime Minister.

The following day, July 25th 1943, when Mussolini reported to the King the outcome of the Grand Council’s deliberations, the Sovereign accepted his resignation. Marshal Pietro Badoglio was appointed the new Prime Minister and Mussolini was taken into the custody of the Royal Carabinieri, primarily to protect him from possible mob violence.

As 1942 drew to a close, it was clear to every Italian staff and field commander that entering the war as allies of Nazi Germany had been a tragic miscalculation. Defeat of the Axis was only a matter of time and, on the home front, support for the fascist regime was rapidly evaporating. The Crown Prince was seen in many quarters, particularly the military, as the only alternative – the leader who had the moral authority to guide the nation out of the dreadful spiral of war. But such an initiative on the part of the Prince – effectively to subvert the authority of the King - would have been unthinkable. He had, after all, spent his entire adult life in the military – obedience to his superiors and obedience to the King had always guided his behavior.

The Prince was dutifully at his post in southern Italy as the climactic crisis of July 1943 began to unfold. It coincided with the first landing of Allied troops in eastern Sicily. By the 24th of July, Mussolini was persuaded to convene the highest consultative and political body of the state, the so-called Grand Council. It was composed of some 28 senior authorities of the fascist regime and had not met for more than four years. In the course of a stormy ten-hour session it voted, by an overwhelming majority, to request Mussolini to relinquish command of the Armed Forces, to call for the King to become again Supreme Commander and to resume his duties and responsibilities –– duties and responsibilities that had never been officially abolished and had been enshrined in the “Statuto”, the Kingdom’s Constitution, since 1848. The King, at last, had a juridical and constitutional opportunity to replace the government that had ruled Italy for over twenty years. He did so by naming a cabinet of non-political ‘technical’ ministers headed by Marshal Pietro Badoglio as Prime Minister.

The following day, July 25th 1943, when Mussolini reported to the King the outcome of the Grand Council’s deliberations, the Sovereign accepted his resignation. Marshal Pietro Badoglio was appointed the new Prime Minister and Mussolini was taken into the custody of the Royal Carabinieri, primarily to protect him from possible mob violence.

|

The King made it clear to all that the first function of the new government would be the ending of hostilities. On September 3d in the village of Cassibile, in Sicily, Italian plenipotentiaries signed a unilateral and unconditional surrender; it placed the Italian military in a ‘non-belligerent’ status but, de-facto, in an adversarial position vis-à-vis the German army, now an ex-ally. These forces, already present in Italy in substantial numbers, had been progressively strengthened during the preceding month. In view of this all-important reality, announcement of the armistice at Cassibile was purposely delayed in order to plan and deploy an effective defense of the capital against German occupation. This would have involved an American operation by the 82d Airborne Division under General Maxwell Taylor in coordination with units of the Royal Italian Army already in Rome under General Giacomo Carboni. At this crucial juncture, everything seemed to go wrong: neither side was clear about the other’s intention – on the timing of the military action and the release of the armistice announcement. Moreover, on the Allied side, there was a distinct (as later became evident) justified mistrust of Carboni’s commitment…precious time was wasted and nothing happened.

By the time the King and Badoglio formally announced the armistice – the 8th of September – Rome was virtually encircled by German forces with no hope of resistance. The Crown Prince was called to Rome from his field headquarters in Anagni and, at dawn, the next day, a party composed of the Royal Family – but only the King, Queen and Crown Prince – the Prime Minister, Badoglio, three ministers and a handful of adjutants exited the capital by car, making their way south along the Via Tiburtina, the only major road known not to be under German control. The convoy, with an escort of Royal Carabinieri, traveled in Court staff cars, all officers in uniform and with Royal insignia flying. |

|

This event, the most critical of all to occur that fateful summer, is, to this day, still the subject of impassioned controversy. Branded a “flight” by all anti-monarchist readings, there can be no doubt that it contributed to the post-war demise of Savoia rule in Italy. However, a more dispassionate, and ultimately more historically correct

view emerges when considering the King’s two overriding concerns after the stipulation of the armistice. These have been amply documented and can easily be summarized as: - Avoidance of further bloodshed to the Italian military and civilian population; an imperative clearly enunciated by the Vatican as well. - Survival of the Italian State personified in the Crown and its ministers. Remaining in Rome after it became clear that it could not be effectively defended, would have negated both of these concerns so critical to the King: thousands would have perished in the streets of Rome attempting to save their monarch.When the Germans would inevitably have prevailed, whatever remained of an independent Italian State would surely have been ruthlessly erased; including the Royal Family. The blame for the fall of Rome to the Germans and the displacement of the Government rests with many, but none as heavily as on the heads of Prime Minister Badoglio and General Carboni. Neither of the two was, by temperament, training, and character up to the challenge that the desperate situation imposed. Both men failed their Sovereign and, ultimately, their country. |

|

The southern city of Brindisi was chosen as the seat of the Government after it was ascertained that it was fully within Italian jurisdiction – that is, not occupied by either German or Allied forces. After the installation of the Royal Family and the remnants of the Government in Brindisi, the Crown Prince emerged as the principal guarantor to the Allies of the terms of the armistice. Their trust in him grew even as he was making no secret of his oft-repeated desire to return to Rome in a heroic last-ditch effort to free the capital of the Nazis. This, of course, his father the King vehemently forbade – not least because, with the death of the Prince, it might well have spelled the definitive end of the dynasty.

During the months in Brindisi, Umberto was able very effectively to knit together units of the Italian Army into efficient collaborators of the Allied efforts to liberate the peninsula from its German occupiers. These units were particularly helpful in intelligence and behind-the-lines missions. He was instrumental in denying Hitler the remnants of the Royal Italian Navy by directing it safely to Malta. The Prince was ever eager to participate in the field and, as General Mark Clark, 5th Army commander remarked, “Umberto, as representative of the House of Savoy, was not only ready to fall in battle against the Nazis, but in a number of instances he appeared to deliberately seek this end.” As his responsibilities grew, so did his prestige in military and political circles: more and more, people were able to appreciate the Prince’s intelligence, perception, tact and honesty. However, never once, even in this difficult period, did the Prince’s total obedience and respect for his father, the King, ever waver. |

|

As the liberation of Rome approached, it became clear that the Allies did not want Victor Emmanuel III to return there as sovereign: he was 74 years old - of which he had reigned for 43. Above all, of course, they felt that he had been irremediably compromised by his submission to, if not active support of, the fascist regime. As the Eternal City once again became the capital of Italy on June 4, 1944, Umberto of Savoy, Prince of Piedmont, assumed the title of ‘Lieutenant General of the Realm’ becoming the de-facto head of state. Although his father at this point withdrew to private life, he did not formally abdicate until May 1946.

By this rapid succession of climactic events, the Crown Prince found himself thrust into a position of immense responsibility at a dramatic moment in his nation’s life: its territory was still divided by a fiercely fought front above the capital, the war had devastated the country’s infrastructure and impoverished its people, not to mention causing huge loss of human life and irreparable damage to cultural patrimony. From early adulthood, the Crown Prince had purposely been kept at a distance from the workings of government and politics. The fascist regime had always deeply distrusted his and his wife’s loyalty to its principles; the regime was thus perfectly happy to relegate both the Prince and Princess of Piedmont to purely honorific duties. Umberto’s own retiring character and strict military upbringing prevented him from ever deviating from the obedience imposed upon him. |

|

From the moment Prince Umberto returned to Rome as effective Head of State in May 1944, he assiduously pursued the pacification and normalization of political life in post-war Italy. The parties that had been suppressed and their representatives, many of whom had been banished during the fascist regime, resumed their role in proposing and promoting public policy. The majority, of course, joined the discourse from staunchly anti-monarchist positions. Umberto’s tenure as Lieutenant General of the Realm was, from the very beginning, fraught with challenges and provocations from these diverse factions. Nevertheless, the governments that were formed under his authority scrupulously reflected the widest possible spectrum of public opinion. At the same time, at least until the end of the conflict in 1945, the Prince tirelessly alternated his duties in Rome with visits to units of the military that were advancing north with the Allied forces. He was also a strong advocate for the thousands of Italian refugees and prisoners of war who were being displaced and for whom almost no one cared. In all of these activities, political, military and humanitarian, the Prince participated with a sense of duty and selfless devotion that was universally admired, even by his most ardent rivals. There is not a document or memory dating to those troubled times that criticizes the Prince – if not for an excess of civility and consideration: an admirable legacy that the history of subsequent events has only enhanced.

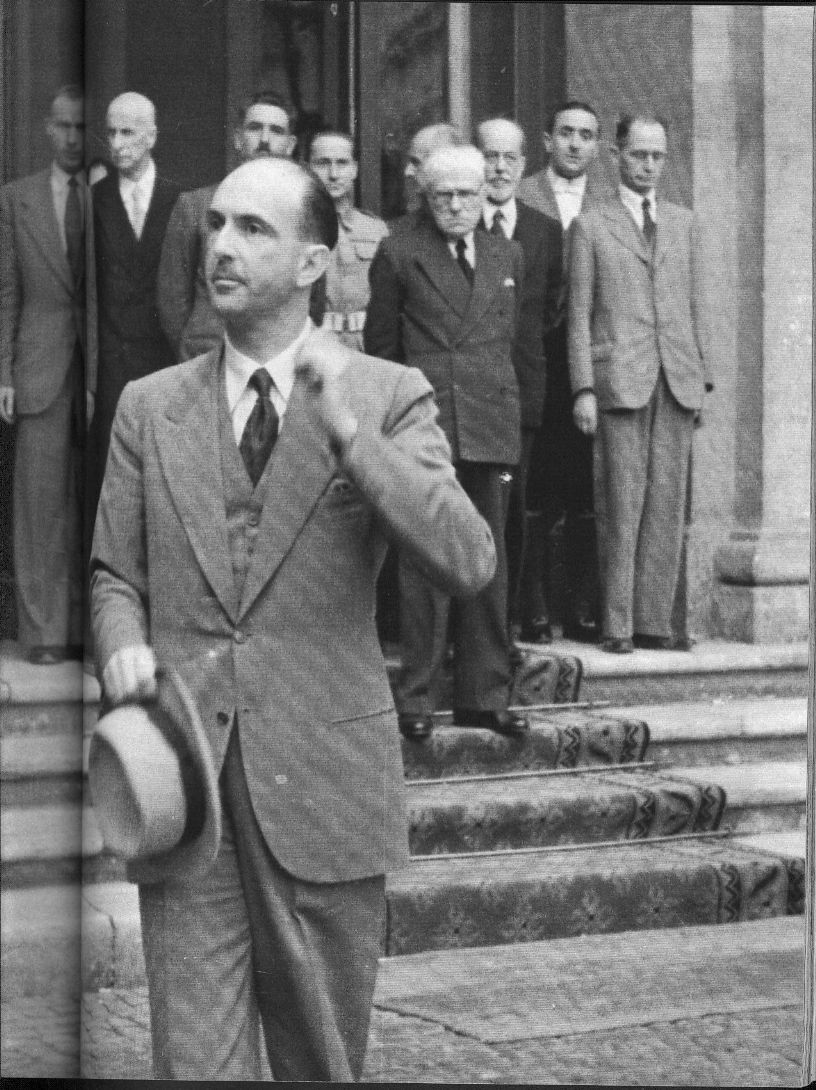

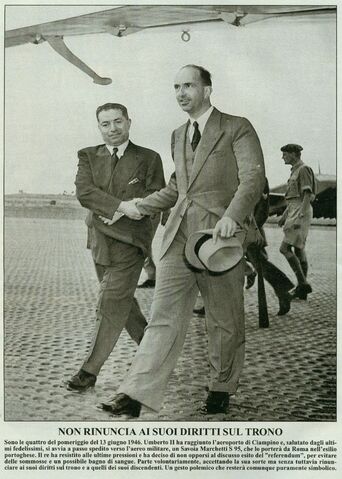

In early 1946, the Crown Prince in the fullness of his authority as the Head of State, took the remarkable step of, himself, signing the decree promulgating a national referendum on the future of the monarchy, a proposal he had already advanced two years previously! Umberto knew that only by submitting this basic issue to a general vote, would the deep wounds of war begin to heal. Thus, on June 2, 1946, the nation was called to the polls: on the ballot was the institutional question of monarchy vs. republic followed by the names of the candidates who would represent their parties at the Constituent Assembly.

Less than a month before the vote, King Victor Emanuel III, at the villa near Naples where he had lived in retirement for nearly three years, signed a brief declaration abdicating the Crown in favor of his son Prince Umberto. Thereupon, with Queen Elena, he embarked on a Royal Navy ship for a self-imposed exile in Egypt. The thirty-five day reign of King Umberto II had begun. |

|

The most telling and moving expression of the King’s feelings at this sad moment can be found in his own words; indeed, it is worth citing the salient parts of his declaration addressed to the Italian people on his departure: “ Suddenly, this night, in disregard of law and the sovereign, independent authority of the Judiciary, the Government, by a revolutionary, arbitrary and unilateral gesture, has assumed powers which do not pertain to it. In doing so, it has placed me in the position of either causing bloodshed or submitting to violent coercion…. I wish to emphasize by my example the following exhortation to all those who maintain their allegiance to the Monarchy, to all those who’s spirit is repelled by injustice: avoid at all costs an escalation of dissent. It would imperil the unity of our nation, fruit of the sacrifice and faith of our fathers….With a sorrowful heart but with the serene conscience of having exerted every effort to fulfill my duties, I take leave of my homeland. Those that have sworn fealty to the King and have kept faith through terrible trials should consider themselves absolved from that oath… but not free of the oath to their country. My thoughts turn to those who have fallen in the name of Italy and my salute is to all Italians. Whatever awaits our country for the future, it can always count on me as the most devoted of its sons. Viva l’Italia!’

On June 18th, the Corte di Cassazione pronounced its findings on the referendum confirming the earlier figures. Significantly, however, its President never issued a declaration formally abolishing the monarchy. Thus, paradoxically, the Republic that was born in those days and has flourished ever since with undeniable success, was, in fact, never officially proclaimed! By the same token, Umberto departed on his lifelong exile as King, no longer perhaps King of Italy, for that had become a republic, but King nonetheless until the end of his days, for he had never abdicated. Years later he would say: “a King can only abdicate in favor of another King”.No better manifestation of the King’s intimate convictions about the symbolic and spiritual values associated with his title can be seen than in the way he lived the almost forty long years of exile. The dignity of his behavior, the thoughtfulness of his writings and pronouncements, his generosity and kindness and, finally, the love of his country that never dimmed or wavered, served as inspiration to legions of loyal admirers of all political persuasions. |

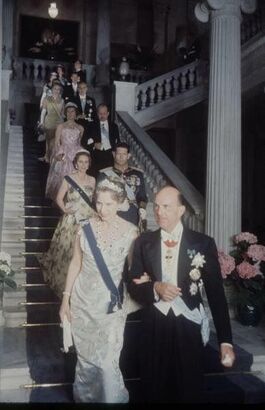

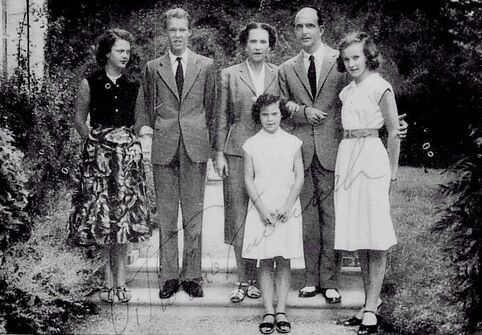

The Royal Family in Exile in Switzerland circa 1950s

The Royal Family in Exile in Switzerland circa 1950s

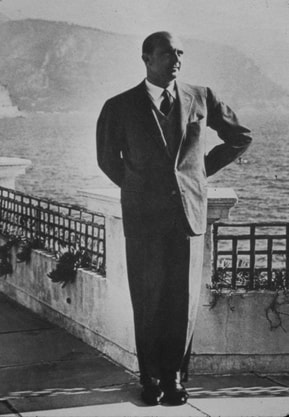

At his ‘Villa Italia’ in Cascais, near Lisbon, he would happily receive fellow-Italians who might share news of his homeland with him, occasionally granting aid to some needy individual or cause, and, if he felt the occasion warranted it, sending members of the Royal Household to represent him. Any initiative, public or private, was invariably undertaken with studied discretion and delicacy.

Studious by nature, the King continued in exile the intellectual pursuits that had always held his attention: whereas Victor Emanuel, his father, had been one of the world’s great numismatists, Umberto’s passion, from his childhood, was the iconography of the House of Savoy. Throughout his life, he persevered as an avid collector in this area and, like all collectors, took enormous pleasure in finding and securing a choice rarity. He was also a knowledgeable connoisseur of European decorative arts.

Despite having created at ‘Villa Italia’ an environment of withdrawn elegance and culture, King Umberto did not avoid traveling, particularly if it put him in touch with Italian emigrant communities and their problems. As perhaps Italy’s most famous and distinguished expatriate, he understood the plight of a life lived far one’s spiritual roots. Wherever he visited, he was invariably received with the deference and attention due to dignitaries of the highest rank – this, despite the fact that he always made a point of traveling as, simply, “the Count of Sarre”.

Studious by nature, the King continued in exile the intellectual pursuits that had always held his attention: whereas Victor Emanuel, his father, had been one of the world’s great numismatists, Umberto’s passion, from his childhood, was the iconography of the House of Savoy. Throughout his life, he persevered as an avid collector in this area and, like all collectors, took enormous pleasure in finding and securing a choice rarity. He was also a knowledgeable connoisseur of European decorative arts.

Despite having created at ‘Villa Italia’ an environment of withdrawn elegance and culture, King Umberto did not avoid traveling, particularly if it put him in touch with Italian emigrant communities and their problems. As perhaps Italy’s most famous and distinguished expatriate, he understood the plight of a life lived far one’s spiritual roots. Wherever he visited, he was invariably received with the deference and attention due to dignitaries of the highest rank – this, despite the fact that he always made a point of traveling as, simply, “the Count of Sarre”.

1955 Pre-wedding Reception for Princess Maria-Pia of Savoy and Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia at the Palace Hotel of Estoril, Portugal for 2500 guests

1955 Pre-wedding Reception for Princess Maria-Pia of Savoy and Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia at the Palace Hotel of Estoril, Portugal for 2500 guests

As Americans, we might do well to recall the King’s visit to New York just about forty years ago. On September 14, 1963 King Umberto arrived at Idlewild Airport – as JFK was then called. It was his first visit to our shores and his itinerary comprised visits to a number of US cities, including Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Here, he was received by Francis Cardinal Spellman, and, in the days spent in New York, the King participated in a great variety of events. Some were very public, such as his appearance at the annual Alfred E. Smith Dinner where he was the guest of Honor and spoke movingly about the importance of the Catholic charities supported by the Cardinal. Other events were more private such as meetings with leaders in the worlds of finance, government and the media. Among others, he met with Henry R. Luce, Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Mrs. Joseph Kennedy, the President’s mother. The King’s days were filled with visits to cultural institutions and to the homes of friends and acquaintances. At the United Nations, the King was received by the Secretary General, U Thant, with whom he spoke at length; several days later he was at former President Eisenhower’s home in Gettysburg, Virginia. Those who attended last year’s Savoy history lecture at the Knickerbocker Club will be interested to know that, on November 5, 1963, Umberto was a lunch guest there of a group of prominent New Yorkers. Not surprisingly, however, the King received his most enthusiastic receptions from the large groups Americans of Italian descent that gathered wherever he was scheduled to visit.

|

On the 9th of October, 1963, tragedy struck in Northern Italy when a dam burst above the Vajont Valley, near Udine, inundating the town of Longarone and many nearby villages. There were more that 1500 victims making it one of the worst disasters of the post-war era. The tragic event cast a pall on the King’s visit and hastened his departure. He never felt closer to his people than in moments of suffering and distress: there is ample and repeated testimony of how he personally, or through his emissaries, reached out to offer assistance and comfort. A genuine generosity and nobility of spirit moved him and its manifestations were invariably private and discreet.

In 1967, as the last stop on a journey that took him to the principal archaeological sites of Latin America, the King was once again in New York. It was brief, and rather more informal than his previous visit; an opportunity, nonetheless, to greet old friends and reunite with members of the Italian-American community. As always, the King was much admired for his simplicity and cordiality and, yet again, demonstrated his concern for his homeland by making a significant personal contribution to the relief fund for the city of Florence. In fact, a few months earlier, that great cultural capital had been the victim of a devastating flood. There can be no doubt, however, that King Umberto, despite the impeccable surface, always harbored a deep, underlying unhappiness about the cruel separation from his beloved homeland. In his later years, as he battled courageously with an implacable illness, the Republic inflicted the ultimate cruelty by denying him the right to die on Italian soil. Some have argued, perhaps correctly, that such a return in extremis and in the wake of an outpouring of pity might have robbed – if not the man – then surely the monarch, of some of the dignity that Umberto maintained, unalloyed, until the very end. |

|

He now lies, as he wished, in the Royal Abbey of Hautecombe, next to Queen Maria Josè and near his ancestor King Carlo Felice of Sardinia and other Counts and Dukes of Savoy who, through the centuries, shaped the history of the House of Savoy. One can only hope that one day Umberto II, Victor Emanuel III and their spouses will, as Kings and Queens of Italy, find their final and most fitting resting place in the Roman Pantheon, together with the tombs of their august predecessors, Victor Emanuel II and Umberto I. Until that happens, the Italian Republic will be depriving its citizens of the full history of the nation, particularly the remarkable and inspiring story of its unification in the 19th Century, a story in which the House of Savoy played a pivotal role. The last two Kings are an integral part of that history; most critically, Umberto, who through his selfless and heroic actions, always put the unity of the nation above all other considerations. They can not be erased from history and they must not be forgotten.

|

Royal House |

History |

Orders |

Members |

News & Events |