American Delegation of Savoy Orders

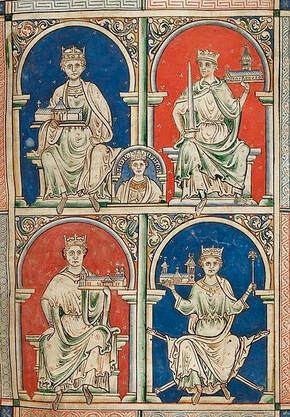

The House of Savoy: Thirteenth Century England

and the Medieval European Community -

The Savoia at the Court of Henry III of England (1216 - 1272)

|

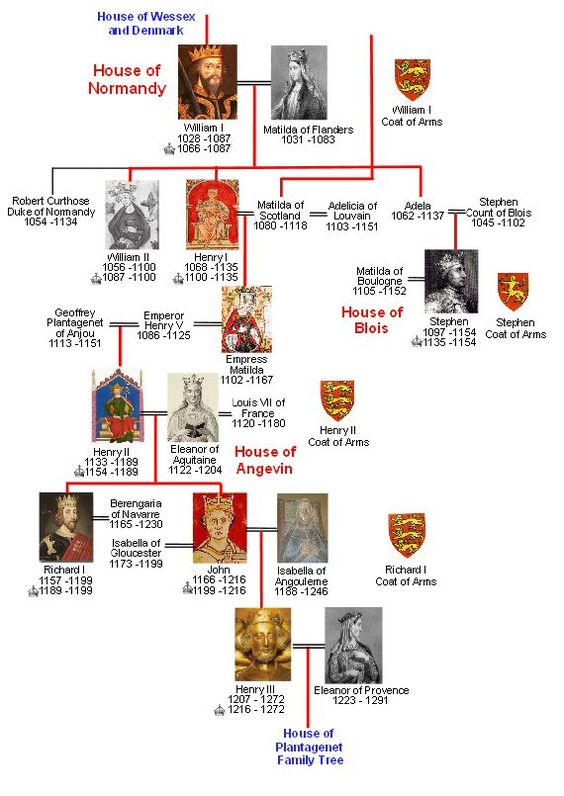

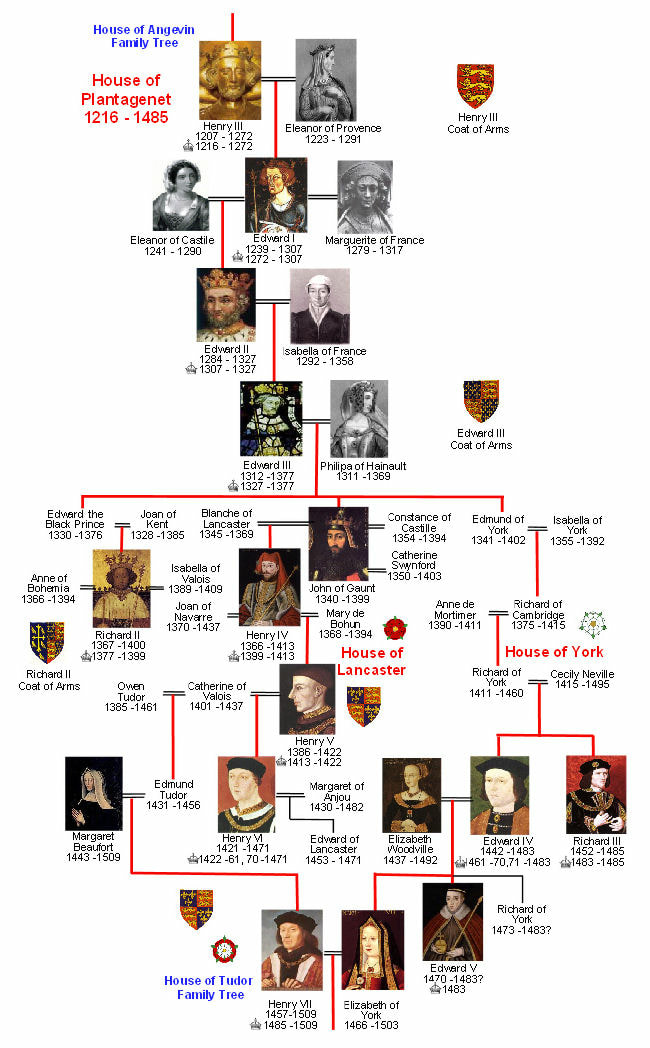

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204) is one of the most remarkable figures of the High Middle Ages. She was daughter and sole heiress of William, Duke of Aquitaine. Barely fifteen, Eleanor married the future King Louis VII of France and, as Queen of the Franks, she participated in the Second Crusade. Upon returning to France, she managed to have her marriage annulled and promptly married the much younger Duke of the Normans, Henry II. When Henry ascended the English throne in 1154, Eleanor became queen a second time! She bore Henry eight children, two of whom would become kings of England: King Richard “the Lionheart” and his younger brother King John. It was John who, under duress, consented to sign the ‘Magna Carta’ in 1215 granting certain fundamental rights to his subjects. This document, and the precedent it set, has been rightly regarded as the foundation for much of European law.

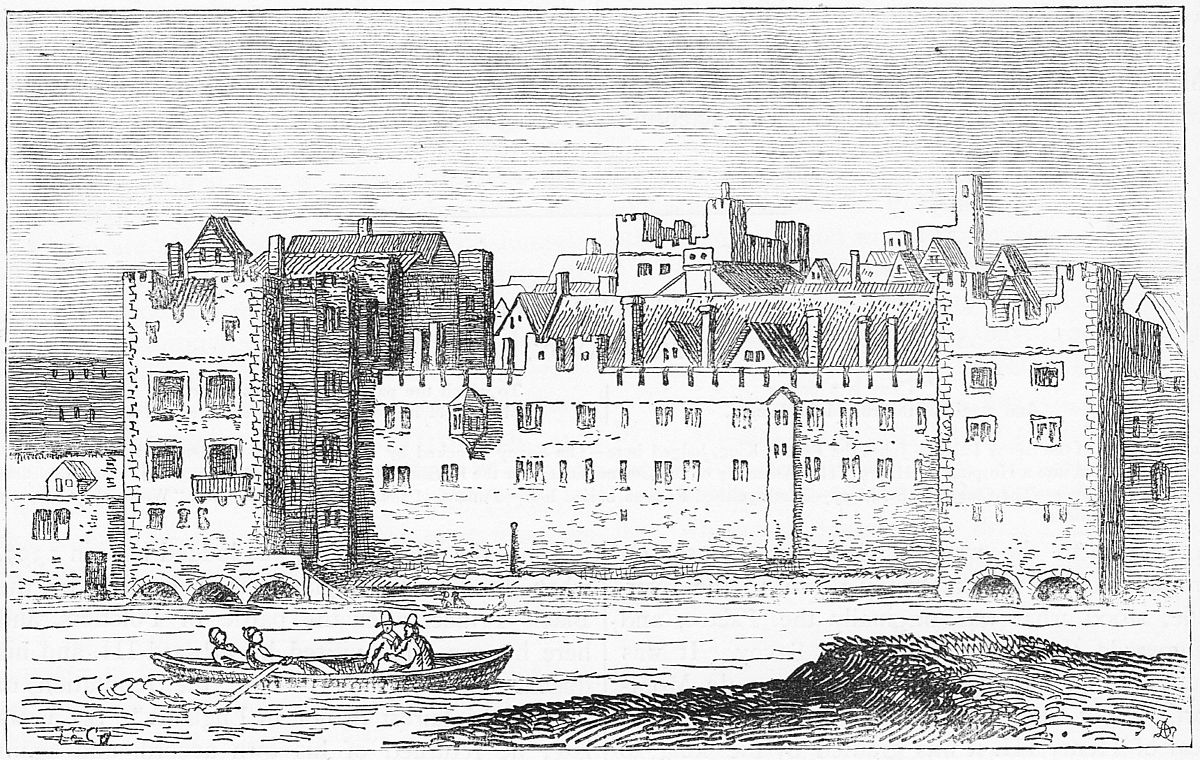

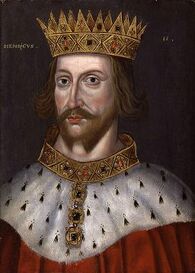

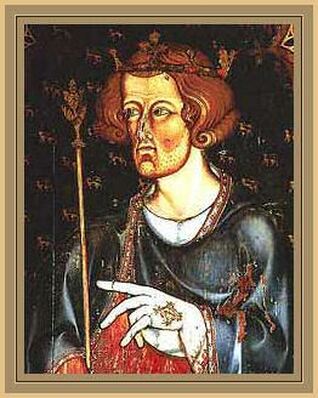

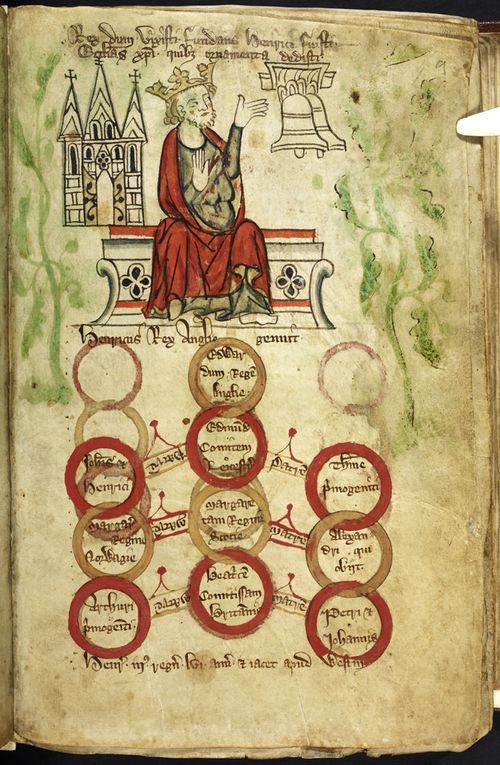

Henry, John’s son, ascended the throne of England as a boy in 1216 and ruled as King Henry III for fifty-six years. He married Eleanor of Provence, one of the four daughters and heiresses of Raymond, Count of Provence, by his wife, Beatrice of Savoy. Henry did not forget about his wife’s Savoia connections and brought his Eleanor’s uncles – Peter of Savoy and Boniface of Savoy – to England. Peter was invested with the highest English title at that time: the earldom of Richmond. Henry named Peter’s brother Boniface Archbishop of Canterbury. Members of the Savoy family were, therefore, to play significant roles during this, one of English history’s most important periods. Henry also assigned land and buildings in London to Peter of Savoy and they became the Savoy Palace – a legacy that survives to this day in the legendary hotel, theater and mediaeval chapel, all bearing the Savoy name on exactly the same historic site. Professor Tyerman’s lecture brings to life the extraordinary people and stirring events that marked this fascinating moment of mediaeval history. Professor Christopher Tyerman A recognized authority on mediaeval history, Professor Tyerman is the author of a number of important scholarly works, among them: God’s War: a New History of the Crusades, England and the Crusades and the eight-volume Who’s Who in Early Mediaeval England. Professor Tyerman is currently on the faculty of Hertford College and New College, Oxford. |

|

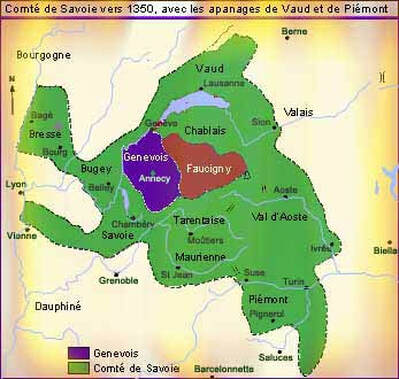

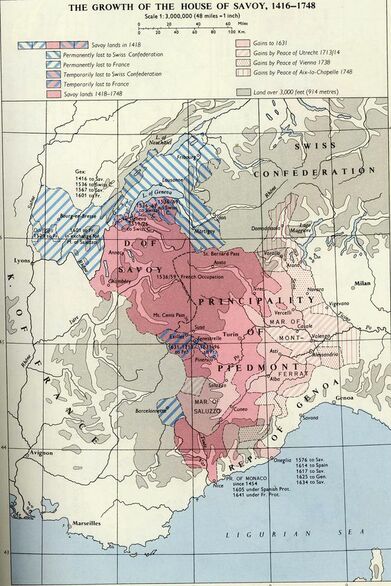

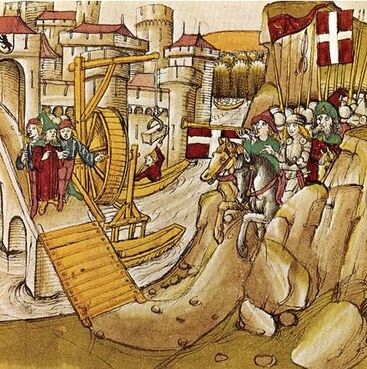

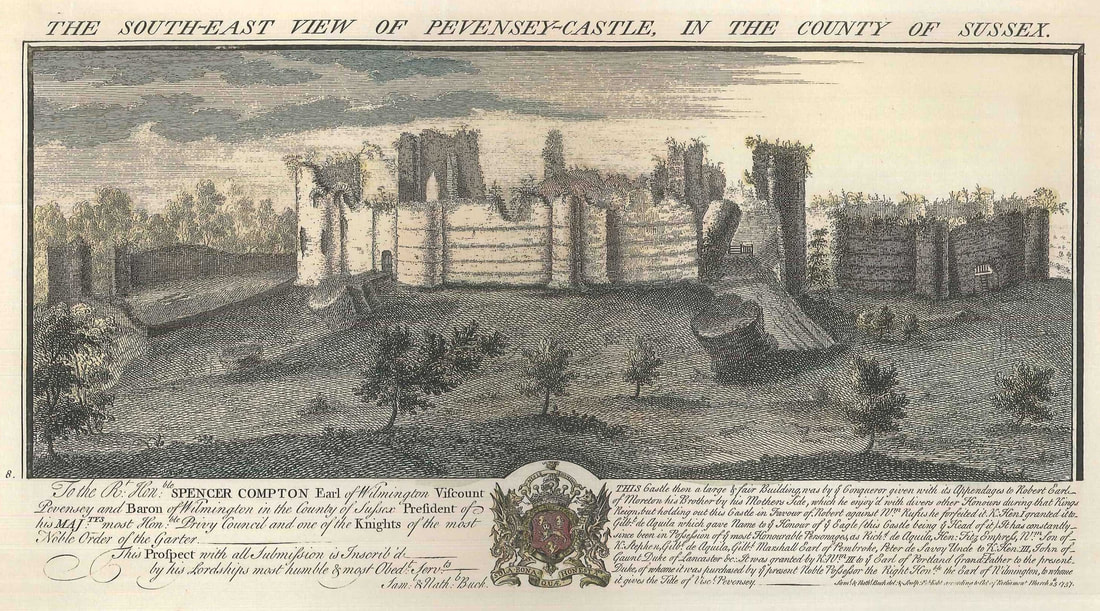

During the night of 17 September exactly two hundred and fifty years ago, in 1759, a British expeditionary force was ferrying itself across the great St Lawrence River preparatory to climbing the cliffs opposite to surprise a French army defending their garrison at Quebec. In one of the boats, the young thirty-two year old British commanding officer recited from memory most of a poem that had been published only a few years earlier to great popular enthusiasm in England. The story goes that when he had finished, General James Wolfe remarked to his companions: `I would prefer being the author of that poem to the glory of beating the French tomorrow'. The poem was Thomas Gray's Elegy in a Country Churchyard, `The curfew tolls the knell of parting day/The lowing herd winds slowly o'er the lea/The ploughman homeward plods his weary way/And leaves the world to darkness and to me'. The churchyard was at Stoke Poges, in Buckinghamshire in southern England. The village's name derived from the family that owned it five centuries earlier, that of Imbert Pugeys from Savoy who had first come to England in the train of Eleanor of Provence when she came to many King Henry III in 1236. Imbert was one of over 170 Savoyards who sought their fortunes in England in the thirteenth century, an aristocratic immigration led by Queen Eleanor's talented, energetic, entrepreneurial and acquisitive uncles, the sons of Count Thomas I of Savoy. They, like their fellow countryman Imbert Pugeys, successfully sought fame and fortune through the patronage of the king of England. All of them demonstrate the fluid and porous nature of noble society and the cosmopolitan character of the courts of the great kings and princes of Europe. Unlike Imbert Pugeys, however, for the ambitious sons of the count of Savoy, preferment in England constituted just one element in an international portfolio of interests, property and offices. How had this come about? Who were these princes from Savoy? What does their experience reveal of the community of western Europe of their time? And what, if anything, do their careers reveal of the origins of the nation state. The lands of the county of Savoy in the thirteenth century straddled some of the major passes and routes for commerce, pilgrims and armies across the western Alps, some of the most important channels for the transmission of men, goods and ideas between the rich Mediterranean world and the increasingly prosperous and commercialized consumer society of north western Europe. Despite this strategically important position, the counts needed to exercise constant vigilance both to protect what they held and extend their possessions west towards the Rhone valley, south west into Provence, northwards into the Pays de Vaud and the Franche Comté, and south into Piedmont and the valley of the Po. Savoy's geographical position offered both advantages and risks situated as it was between areas of absent, contested or imploded political power. In theory, the counts overlords were the Holy Roman Emperors of the house of Hohenstaufen, technically rulers of what is now Germany, Switzerland, North Italy and the region between the Alps, the Rhone and the Mediterranean. In fact imperial power was distant and repeatedly challenged in the south by the cities and counts of Lombardy, usually encouraged by the popes in Rome. In the Alpine region local dynasties, such as the Savoyards in the west or the Habsburgs to the east, were forging independent statelets, sometimes with but often without direct imperial approval. Further west the growing power of the kings of France added to a complex mosaic of competing political interests and jurisdictions. This confused and shifting picture provided both opportunities and risks to the counts of Savoy as it placed them literally, dynastically and politically at the centre of some of the fiercest international conflicts of the age: the thirty years' war between the papacy and the Hohenstaufen emperors from the 1230s to 1260s that tore apart Italy and Germany; the competition for control of Provence after the 1220s, in the aftermath of the Languedoc wars known as the Albigensian crusades; and the contest between the kings of England and France for control of much of southern and western France. To succeed, the counts of Savoy needed to find alliances across these divides without provoking one side or another to regard them as enemies. The same fragmentation of power that allowed the counts to extend their control in the region, simultaneously threatened them with potential extinction. In all competitions, there are winners and losers. In thirteenth century international politics, there were spectacular examples of both, some uncomfortably close to the house and lands of Savoy. |

|

The cheapest and often most lasting way for any thirteenth century ruler both to protect existing interests and to expand authority was by marriage alliances, political negotiation, and the use of ecclesiastical preferment as church office usually carried with its substantial income and extensive rights of local jurisdiction. Families were the chief commodities in this power market; sons to marry heiresses; sons to scale the prosperous and influential heights of the ecclesiastical job market; and daughters to forge lucrative alliances and open up career prospects with neighbours and distant powers. Of this commodity, Savoy possessed an abundance. Count Thomas I and his wife Margaret of Geneva had ten children that reached adulthood; eight boys and two girls. All but one of them fulfilled their destinies in church and state (often simultaneously) or in the marriage bed, their possessions, contacts, and families spread across Europe from Ireland to Sicily in a diaspora of lasting significance for the creation of a secure Savoyard state and the fate of four nations, Italy, Germany, France and England, their achievements and lives vividly demonstrating how the medieval international system worked. Of the sons, the elder three, Amadeus, who succeeded his father as count in 1233, Humbert and Aymon, concentrated their activities within Savoy. The region was clearly not large enough to offer immediate secular preferment for the five younger sons, so all of them began their careers receiving church offices, even though only one of them, Boniface, ever actually took full holy orders. This allowed the Savoy princes to be paid by other sources than the comital revenues and lands, a neat and effective system of dynastic economy. Not all church posts were associated with cure of souls, being, like diocesan archdeacons and deans and canons of cathedrals, largely administrative. Equally, being elected a bishop- as the fourth son William was in 1226 at Valence in the Dauphiné- meant that the bishop-elect could enjoy the fruits and power of the office before being made a priest and consecrated. Frequently, such bishops never entered into the full spiritual obligations of their positions. The term `clerk', 'clericus', in the Middle Ages was not a synonym of priest. William, bishop-elect though he was, pursued a vigorous secular political career in England and an active military one in Italy where in 1238 he personally led an army in support of the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II, actually fighting on the field of battle, earning himself the epithet form one disapproving observer as a `man of blood'. The fifth child, Thomas, also originally a cleric, soon abandoned the church as a route to fortune, beginning at the court of Louis IX of France in 1234. One of the consistent descriptions applied to these brothers, even by hostile witnesses such as the English chronicler Matthew Paris, was that they were strikingly good looking. At a time when some saw the face as the mirror of the soul, and an heiress could attract large numbers of suitors, this was no disadvantage. Thomas, at least, seems to have exploited whatever charms he possessed, in 1237 securing the hand of the widowed countess of Flanders. The county of Flanders was one of the richest principalities in all Europe, thanks to its cloth industry, and Thomas, count by virtue of his marriage from 1237 to 1244, took full advantage, securing revenues and income that lasted even after his wife's death deprived him of the comital title. Armed with this Flemish money, Thomas not only operated in northern Europe but after 1244 transferred his activities to northern Italy where another grand marriage secured him a prominent position in the febrile politics of Piedmont and the Po Valley. |

|

|

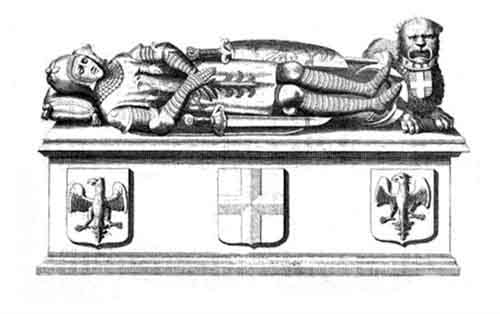

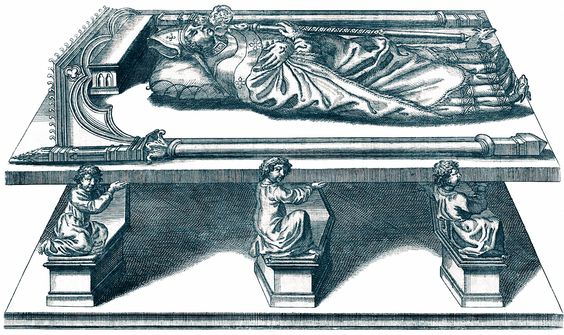

The careers of two of the younger brothers were almost minor images of those of William and Thomas. Peter, the sixth son, like Thomas, began as a cleric, as a canon of Lausanne. In 1233, however, he was betrothed to a local heiress and spent much of the rest of his career carving out a domain in the western Alps. In 1240, however, he followed his brothers William and Thomas to England where he amassed huge estates and for the next quarter of a century divided his time between England and Savoy, before, in 1263, finally inheriting the county of Savoy itself from a nephew. By contrast, Philip, the youngest brother, followed William's precedent and remained in the circle of church promotion, succeeding his brother as bishop-elect of Valence in 1241 before being elevated to the archbishopric of Lyons in 1245, a major position enhanced by the residence there of the exiled pope Innocent IV. At the height of his church career, after over 25 years of preferment, Philip was the incumbent simultaneously of five parishes, one canonry, one provostship, two deaneries, one bishopric and one archbishopric, spread over much of western Europe, yet he was never ordained a priest and, as his brothers died off, he too turned his attention to the secular sphere, marrying the rich heiress of the county of Burgundy in 1267 and succeeding his brother Peter as count of Savoy in 1268. The only Savoyard to display genuine religious commitment was Boniface. Briefly a Carthusian monk, after preferment in Savoy he reaped the reward of family ties with his elevation to the archbishopric of Canterbury in 1241, actually submitting to ordination in 1244, thereby debarring himself from the comital succession in Savoy. Boniface was no less an active secular politician on the continent as in England, but he maintained a consistent and vigorous defense of his archiepiscopal rights and those of the church in general. The most striking feature of these careers was their flexibility- between church and state, council chamber, military camp and cathedral- and their easy range across the continent. There were two magnets of preferment. One, which was never far from the aspirations of the Savoyards, was centred on the county itself. Collectively, the Savoy family business extended its influence and possessions on all fronts on both sides of the Alps and managed to remain in favour- collectively if not always individually- with the papacy and the imperialists whose rivalries dominated the surrounding regions. By spreading their possessions and preferment across Europe, these brothers ensured that at least some members of the Savoy house would be on whatever was the winning side, a trick that only worked if they made themselves useful to their patrons, not least in the complex dance of diplomacy. However, none of the brothers lost contact with their homelands despite the grandeur of some of their posts elsewhere. Other thirteenth century families displayed a similar restless cosmopolitan acquisitiveness but none displayed so strongly this consistent bifurcation of interests. The second magnet was, ironically perhaps in a dynasty of so many men, entirely dependent on the women of the family who, in most cases, belied the literary fiction of passive femininity. The marriage of the youngest daughter of Thomas I, Margaret, materially helped in the acquisition of the Pays de Vaud north of Lake Geneva, long a target of Savoyard ambitions. Of far greater significance, in 1219 Margaret's older sister, Beatrice, married Raymond Berengar V, count of Provence. Immediately, this drew the Savoyards into the politics and preferment opportunities of that region and into the conflicts that were defining the future of southern France; the consequences of the Albigensian crusades being fought just to the west in Languedoc; the contest between the kings of England and France over the legacy of English lands in France lost by King John a generation earlier; and the encroachment by the Capetian French kings into the rich lands beside the Mediterranean. The policy of and succession to Provence played a pivotal role in all of these. And Beatrice, by no means a blushing violet, played a significant part in settling both. Of even greater significance for the Savoyards, Beatrice and Raymond Berengar produced four daughters, conventionally lauded for their exceptional beauty (few successful well-born medieval women –or men come to that-were described as being plain or ugly), but far more notable for their spectacular marriages. Each one married a king or a man who went on to become a king. Margaret, the eldest, married Louis IX of France in 1234. Two years later, in 1236, Eleanor married Henry III of England. In 1242, as part of attempts to resolve continued tensions in southern France, Sanchia, the third sister, married Henry III's brother, Richard, earl of Cornwall who, in 1257, was elected king of Germany. The youngest sister, Beatrice, on whom the succession to Provence had been settled, was, along with her inheritance, snapped up by Louis IX's youngest brother, Charles duke of Anjou in 1246. Twenty years later, Charles of Anjou, with papal help, conquered southern Italy and Sicily from the Hohenstaufen and became king of Sicily. At least on the first two occasions, in France and England, their nieces' marriages opened up fresh avenues for advancement for the Savoyard brothers which they were not slow to follow. |

|

Before looking more closely at the example of the Savoyards in England, it might be asked what set these Provencal girls apart and why did their royal spouses permit an influx of their new in-laws? The answer to both is politics. Ties of affection in high places are often hard to assess and, from the middle ages, harder to prove. It was said that Henry III fell under the spell of William, bishop-elect of Valence in the three years before the latter's early death in 1239, but this opinion may have been fuelled by the suspicious xenophobic monk of St Alban's, Matthew Paris, whose gossipy compendious contemporary chronicle had little good to say of any foreigner. As to the marriages themselves, then as now such relationships are impossible to penetrate from the outside. Margaret seems to have had a fairly tough time with her pious mother's-boy husband, Louis IX of France, who even allowed his mother to ration his visits to his young wife (they had no children for six years). Margaret also proved herself willing to adopt an independent political line as regards her own extensive contacts with the French nobility and later with her own children. On both occasions she was firmly put in her place, first by her mother-in-law and then her husband. Eleanor's relations with Henry III appeared much more amiable, but that may have been down to Henry's accommodating nature and his willingness to shower favour on Eleanor's relatives and to listen to her advice. In reality, the determinant force behind these marriages was not soap-opera domesticity but political advantage. In the early 1230s both Louis of France and Henry of England were emerging from periods of royal weakness and trouble with groups of great magnates. A marriage to another royal dynasty offered difficulties of precedence. One with any of the great noble families within their kingdoms would threaten the internal balance of factions and patronage. In these situations, alliance with the Provencals (and, through them, with Savoy) possessed obvious attractions. They would not disturb existing political arrangements; they provided an accretion of royal influence through an injection of a new political interest; they avoided angering either pope or emperor; the brides' family, though grand, was no rival, yet the brides' extremely well-connected relatives could- and did- act as energetic international negotiators; and the marriages established connections with two strategic regions –Provence and Savoy- that could play a part in future foreign policy initiatives. Thus the marriages were safe and of potential advantage. There was also the obvious dynastic point: the brides came from evidently fertile stock. |

|

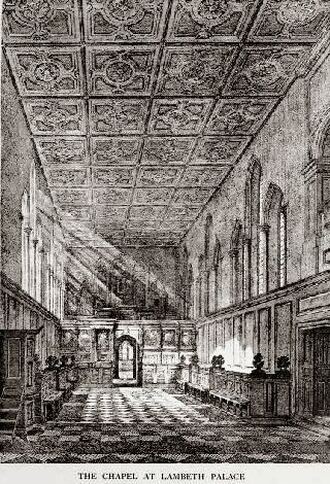

Even more so when we consider, in addition to these grants, those given to the other less exalted Savoyards that flocked to England under Henry III. Of the 170 who are known to have come between 1236 and 1272, before 1258, 32 had received revenues of over 100 marks (£66), 26 grants of lands (including 11 very large estates); 30 were given heiresses or wardships. Of course, some in each category overlapped. Another 60 obtained English church benefices. These figures exclude those who arrived in England under Henry III's son and successor, Edward I. Furthermore, beyond outright gifts, numerous Savoyards found themselves in employment, notably a number of knights in the royal household, including a few who rose to be stewards of the household. About 39 of these economic migrants out of the 170 who arrived actually settled. None of the Savoyard princes did. Their English Eldorado was an essentially colonial experience. Even so, the influx of Savoyards caused loud murmurs of nationalist discontent, much of it unwarranted. Although dependent on royal patronage at the start, both Peter of Savoy and Archbishop Boniface proved to be independent figures in English politics, unafraid to oppose their nephew-in-law when they saw fit. Despite claims of a Savoyard infiltration of English government, between 1241 and 1258, only 14 Savoyard knights and 12 clerks entered royal service at court and all were expelled in 1263 during the English civil wars. Perhaps a dozen or so Savoyard knightly families who came to settle under Henry III survived into the fourteenth century- the Pugeys of Stoke Poges being one. By the second and third generations and free from royal service, these families tended to merge into the minor aristocratic background of rural English landowning. The tangible Savoyard legacy persisted in only a few village names, like Stoke Poges and in the great palace on the Strand that Peter of Savoy built for himself, part of the site of which is occupied by the modern hotel and theatre. Peter's palace was remodelled and extended in the fourteenth century by Henry of Grosmont, earl of Lancaster, but then completely destroyed in 1381 during the Peasants' Revolt. Later rebuilt under royal ownership in the early sixteenth century, the site served as a hospital, barracks, a prison, offices and warehouses. The existing Savoy Chapel dates from the early 16th century and has nothing whatsoever to do with Peter himself. But as with other London names, the shadow of a cosmopolitan medieval past remains: Lombard Street in the City remembers the Italian merchants and banks; St. John’s Wood, where the US Ambassador has his residence, reflects its earlier ownership by the crusading Knights Hospitaller of St. John; and Knightsbridge was an estate of the Knights Templar. |

|

The political role of the Savoyards in England is unmistakable. William provided expert diplomatic advice in the later 1230s. Peter became one of the leading figures at court, playing a prominent role in many of the conflicts that punctuated Henry III’s stuttering rule, while simultaneously pursuing his interest in and around the Alpine region. Boniface proved a vigorous, if frequently absentee archbishop of Canterbury, the last non-Englishman to hold that role to date, rescuing his see from crippling debt, extending archiepiscopal jurisdiction over the English church and defending clerical rights against lay encroachment. On the continent he was clsot to successive popes, even holding the office of commander of the papal guard. Such was his forceful approach to enforcing his rights as archbishop that Matthew Paris spread a damaging story of how in 1250, accompanied by a bodyguard of Provencal thugs, he personally beat up the prior of St. Bartholomew’s Priory in London. Paris also suggested Boniface customarily went about with chain mail under his vestments. Both tales are likely to be spurious but suggest a level of resentment at this foreign princely prelate. This feeling of hostility also attached itself to other Savoyards, such as Peter of Aigueblanche, one of William of Savoy’s secretaries, who became bishop of Hereford (1240-68) and one of Henry III’s most valued officials and diplomats. Unlike his grander countrymen, Peter of Aogueblanche concentrated his activities within England. On the other hand, another Savoyard, Henry of Susa, one of the leading European canon lawyers of his generation, employed until 1243 as Henry III’s chief lawyer in church cases, ranged, like the count’s children, across western Europe, becoming a bishop of Provence and later a cardinal. The careers of the Savoyards in England point to a prominent feature of English political life in the thirteenth century, namely the mismatch between the politics of the royal court and the expectations of the indigenous nobility and political nation. Henry III was descended from the counts of Anjou and dukes of Normandy. He saw himself as a king in the international community of Christendom not just king of England. Although he promoted the cult of the Old English saint, Edward the Confessor, naming his son after him, Henry did not see himself as an Englishman alone or at all. Most of his close relatives were in some senses French. England formed just one section of his inheritance, even if it was the one of the few pieces he actually held. It was entirely fitting that when he died, while his body was interred near the shine of the Confessor in Westminster Abbey, [Henry III] his heart was buried in France, in the Anjou family mausoleum at Fontevraud near the Loire, next to his uncle Richard I and his grandfather Henry II. Henry III's active interests embraced the British Isles, western and southern France. In 1255 he even agreed to try to put his younger son Edmund on the throne of Sicily (a scheme in part brokered by Peter of Savoy). A flavour of this internationalism can be traced in the deal struck by Henry III in 1246 with Amadeus IV of Savoy, negotiated by Amadeus's brother Peter and Peter of Aigueblanche. By this treaty, Amadeus agreed to transfer to Henry III overlord-ship of four strategic castles guarding the Great St Bernard and Mt Cenis passes in return for 1,000 marks and an annual pension of 200 marks. Amadeus would henceforward hold these castles as fiefs of the English crown. Although this apparently quixotic and bizarre agreement was forged in the context of rivalry with France over the inheritance of Provence, it stuck, in 1273 Philip of Savoy, now count, doing homage to the new king Edward I for the castles. Nothing illustrates the fluid internationalism of power and authority better than this acquisition by the English crown of overlord-ship over lands in remote Alpine valleys to which he had absolutely no dynastic claim. It only made sense within Henry III's grand schemes for European dominance. But such acts, as with the cripplingly expensive Sicilian scheme, were greeted with bewilderment, suspicion and ultimately anger by most of the political classes in England who had no interest at all in such far away places and hair-brained schemes; even Richard of Cornwall, married to Queen Eleanor's sister Sanchia, described the plan for an English king of Sicily as like trying to reach the moon. |

|

The gulf between royal international perspectives, as represented by King Henry's easy patronage of his continental relatives, and the more introspective concerns of his subjects fuelled a major political crisis in the late 1250s and 1260s. The collapse of Henry's Sicilian scheme, leaving him with huge debts and no political capital, brought matters to a head. In 1258, Henry was forced to agree to entertain only native born advisers and in 1263 an act of parliament expelled foreigners from public office. In the same year, Queen Eleanor's barge on the Thames was pelted with missiles and garbage by a London mob on London Bridge. However this evident nationalist xenophobia, encouraged by tax demands to pay for Henry's foreign adventures, concealed a more complex state of affairs. In April 1258, seven of the greatest barons in England formed a sworn commune dedicated to reforming the government of the realm and curbing the arbitrary conduct of the king. This opposition led directly to the settlement know as the Provisions of Oxford that attempted to place royal government under supervision of a committee of barons and, explicitly, the advice of native born councillors. Yet two of the seven original reformers who swore the oath of commune in Apri1 1258 were Peter of Savoy and Simon of Montfort, the king's brother-in-law, a Frenchman whose career in many ways mirrored exactly those of the Savoyards. While Henry's incompetence may have provided a public cause for opposition, ironically men like Peter of Savoy –who after all had benefitted enormously from Henry's generosity and had been closely implicated in the detested Sicilian business- were particularly outraged not on behalf of the rights of native born Englishmen but against the favours now being granted by Henry to another, new, rival wave of foreigners, Henry's Lusignan half-brothers. The nationalism apparent in the 1250s and 1260s was thus a fractured nationalism, cross cut with factionalism and political rivalries that owed nothing to national origin. Although largely loyal to Henry III after initial criticism of 1258-9, both Peter and Boniface of Savoy soon faded from the English scene as the civil wars ended in the mid 1260s. Edward I's renewed patronage of Savoyards, such as Othon of Grandson, his oldest personal friend, while significant individually, was on a lesser scale and did not include members of the comital house itself. A number of Savoyards accompanied Edward on his crusade in 1270; others served as constables of his new, strategically vital Welsh castles from the 1280s, a sign of the premium placed by rulers on service by those dependent on the king alone, independent of existing national factions. Some of these families established themselves in the upper echelons of English society; a great nephew of Othon of Grandson, John, was bishop of Exeter for forty years to his death in 1369. Yet, despite the continued English involvement in French and continental politics for the rest of the middle ages and beyond, the close ties with the house of Savoy were never reignited in the way they had been in the thirteenth century. Effectively, with Edward I, a great-grandson of Thomas I of Savoy, the Savoyard episode in England came to an end two generations s after it had begun in the 1230s, the remaining Savoyard families in England slowly merging into the rural lives of country gentlemen. If the memory of the Savoyards in England is scarcely front page news, nonetheless, their activities reveal much of the way international politics and noble society operated. For one thing, their pan-European experience was far from unique. Numerous families from across aristocratic Europe displayed similar restless cosmopolitan acquisitiveness. |

|

Between 1200 and 1300 members of the Champagnois family of Brienne supplied claimants to the throne of Sicily, one king of Jerusalem, one emperor of Constantinople and a duke of Athens. Cadet branches were to be found in prominent court office in France, Italy, Spain and Cyprus. The family of Henry III himself began as provincial counts of Anjou south of the Loire in France before founding dynasties that ruled Jerusalem from 1131 and a vast western European empire that at one stage stretched from Ireland to the Pyrennees, including England from 1154. The Poitevin family of Lusignan provided kings of Jerusalem from the 1180s and of Cyprus from 1192 until the fifteenth century. When one of them married the widow of King John of England, the Lusignans suddenly found themselves intimately connected to the English royal house, their attachment to Henry III's court providing members of the family with titles and lands into the fourteenth century. Like the Savoyards all these families had prospered through crucial strategic marriages. Other French nobles founded principalities in Greece in the thirteenth century, as did Catalans in the fourteenth. The Baltic provided a frontier of profit for Germans and Danes. Italian merchant aristocrats, such as the Sanudi in Naxos, became rulers in a western diaspora across the eastern Mediterranean from the early thirteenth century, the fluid politics of the frontiers of Latin Christendom creating many such opportunities for the ambitious or talented. The Savoyards, however, revealed a parallel fluidity within the settled kingdoms and nations of the west where family and breeding transcended nation as a bond and attraction. The world of European courts was a network of related families always in need of personal support to balance or even oppose local vested interests. In the thirteenth century, this concert or community of Europe was a family affair: Henry III's brothers-in-law included the emperor Frederick II of Germany, Louis IX of France, Charles of Anjou, king of Sicily and Simon of Montfort, son of the commander of the Albigensian crusade that had conquered Languedoc for the king of France. Rather like the European crowned heads at the start of the twentieth century, everyone seemed related to everyone else. The usefulness of the Savoyards lay in their lack of settled or exclusive allegiances, their availability, and their own unrivalled international contacts. Their main attraction was the presumption of loyalty but more importantly their independence from existing entrenched political vested interests. From their perspective, the profits on offer were irresistible but, unlike many other wandering nobles, they retained their interests in their homeland. This is what especially distinguished them from the other successful émigré princes. Theirs was not a form of entrepreneurial proto-colonialism but an intrinsic element of their own domestic scene. |

All European courts were cosmopolitan. The precocious nationalism apparent in England was tempered by the community between the highest ranks of power, where political authority was buttressed not by laws and fixed geographic boundaries but on clientage, networks of alliances and allegiances that were essentially personal and dynastic. The origins of the nation state reveal how there are many ways to define political and national identity, and that nation states are not the inevitable model of government- nor necessarily the most efficacious as European history has shown in the last hundred years. The nation is a construct not an act of providence. Medieval and modern states had and have no pre-destined shape or frontiers. The presence of the Savoyards in England demonstrated the diversity, contingency and negotiable nature of national feeling and state building while, in England, accidentally helping define them more closely. However, these essentially personal bonds of political authority revealed by the Savoyards did not mean that such ties were random or arbitrary or that kings operated outside domestic legal, social and political conventions. Foreigners merely extended the range of royal patronage, enhancing his prestige as well as supplying independent members of a royal affinity who could exert considerable political clout- as did the Savoyards.

The presence of the Savoyards at Henry III's court, and of Peter of Savoy in his grand mansion on the Strand, point to the very different nature of national identity in the high middle ages. Like resentment at modem immigrants in many parts of the world, apparent preferment of supposed foreigners could attract hostility in times of conflict, crisis or dearth and that hostility could be couched in term of nation. The laws and institutions of the state equally were, notably in long-centralised England, similarly self-consciously those of a people distinct from others. But the reality of political life presented a more diverse, fluid, personal and flexible aspect, redolent of mobility and transmission of people and ideas at a level beyond the national. Here is exposed the essentially bifurcated visions of medieval public life- at once intensely parochial and so limitlessly wide that they could embrace in concept, imagination and fact Eurasia, from Ireland and Spain to the Baltic and Russia to the Black Sea, the eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. In a period that witnessed crusades that drew support from a whole continent in the service of a church that claimed, not entirely fancifully, continental jurisdiction, the barriers of geography vanished before a shared culture of noble ambition forming a genuinely cohesive European community, not antithetical to but embracing of individual emergent nations. The ties that bound this community — personal, economic, commercial, religious- transcended even the distinctions between the secular and ecclesiastical, when bishops could lead armies and counts could include tenure as an archbishop in their resumés. Whatever else, there was nothing especially narrow or confined about the lives and experiences of the elites of medieval Europe, as the children and grandchildren of Thomas I Count of Savoy so brightly illustrated.

The presence of the Savoyards at Henry III's court, and of Peter of Savoy in his grand mansion on the Strand, point to the very different nature of national identity in the high middle ages. Like resentment at modem immigrants in many parts of the world, apparent preferment of supposed foreigners could attract hostility in times of conflict, crisis or dearth and that hostility could be couched in term of nation. The laws and institutions of the state equally were, notably in long-centralised England, similarly self-consciously those of a people distinct from others. But the reality of political life presented a more diverse, fluid, personal and flexible aspect, redolent of mobility and transmission of people and ideas at a level beyond the national. Here is exposed the essentially bifurcated visions of medieval public life- at once intensely parochial and so limitlessly wide that they could embrace in concept, imagination and fact Eurasia, from Ireland and Spain to the Baltic and Russia to the Black Sea, the eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. In a period that witnessed crusades that drew support from a whole continent in the service of a church that claimed, not entirely fancifully, continental jurisdiction, the barriers of geography vanished before a shared culture of noble ambition forming a genuinely cohesive European community, not antithetical to but embracing of individual emergent nations. The ties that bound this community — personal, economic, commercial, religious- transcended even the distinctions between the secular and ecclesiastical, when bishops could lead armies and counts could include tenure as an archbishop in their resumés. Whatever else, there was nothing especially narrow or confined about the lives and experiences of the elites of medieval Europe, as the children and grandchildren of Thomas I Count of Savoy so brightly illustrated.

Royal House |

History |

Orders |

Members |

News & Events |