American Delegation of Savoy Orders

Rise of the Savoy-Carignano Branch: 1831

|

The junior branch of the House of Savoy, the Princes of Carignano, was descended from Duke Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy who died in 1630. His second son was Duke Victor Amadeus I and the senior branch was descended from him to King Charles Felix who died in 1831. Duke Charles Emmanuel's fifth son, Thomas, whom he created Prince of Carignano (died 1656), was the progenitor of the Savoy-Carignano line. The celebrated Field Marshal Prince Eugene was a Savoy-Carignano, Thomas' grandson.

The senior member of the Savoy-Carignano branch of the family on the death of Charles Felix was Prince Charles Albert (1798-1849), who succeeded as Twenty-first Duke of Savoy and Seventh King of Sardinia in 1831. Born in Turin in 1798, he had married Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria, daughter of Grand Duke Ferdinand of Tuscany. He was raised as heir presumptive to his cousin and participated in the French campaign to suppress the Spanish insurrection in 1823. The young Charles Albert dazzled the courts of Europe by his good looks, keen intellect and easy manner. Also a patron of the arts and sciences, he was loyal to the church and supportive of its charitable activities. Public monuments were ordered to give Savoyards a sense of history, cities were mapped out along grand avenues, the royal archives and treasures were opened to the public to view, and scientific congresses were sponsored by the King. The chivalric orders were restructured to reflect modern circumstances without, however, diminishing their mission or purpose. The Civil Order of Merit of Savoy was founded on October 29, 1831, to honor those citizens of the realm who were no less important than the military. The King believed that the institutions of a modern state should be available to its citizens. And so he commenced an ambitious building project that transformed the face of Turin. The Royal Library, the Mint, the Treasury, the Gallery of Fine Arts, the Albertine Academy of Fine Arts and the Royal Museum of the Homeland were all instituted in his early years. He also reformed the political system while retaining executive power. With the winds of change sweeping across Europe in the years just prior to 1848, the King was seen as a hope for Italian Unification. He himself questioned the timing of such a movement and was deeply suspicious of the liberal intellectuals who had little concept of realpolitk. The King allowed himself to be drawn into the popular frenzy of national liberation from Austria in the northern part of the Italian peninsula. France, Poland, Austria, The Two Sicilies, Rome and Lombardy were engulfed in Italian nationalism. It seemed that the time was propitious to strike at the Austrians in Lombardy while revolution in Hungary distracted Vienna. Charles Albert led his forces across the Lombard plain and initially defeated the Austrians. But soon, Tsar Nicholas I brought his Cossacks to assist the young Emperor Franz-Josef in restoring order in Hungary, and the Emperor could concentrate on the crisis in his Lombard dominions. Austrian troops under the baton of Field Marshal Radetzky reversed the Piedmontese gains and Charles Albert suffered humiliating defeats at Custozza and Novarra. Lombardy was lost; the King sued for peace and abdicated his throne in 1849. He left for Portugal where he died soon after and was returned to the Basilica of Superga for burial. |

|

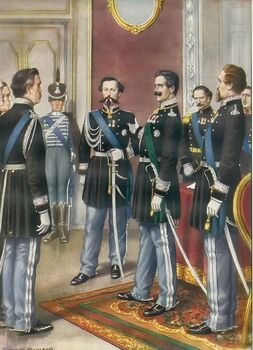

The Twenty-second Duke of Savoy and Eighth King of Sardinia was born March 14, 1820 at the Castle of Stupinigi, where he was raised with his younger brother, Ferdinand, Duke of Genoa, his junior by two years. He was married to Archduchess Maria Adelaide of Austria at the age of twenty-two. Trained in the military with little formal political education, Victor Emmanuel succeeded to the throne of Sardinia on the abdication of his father, King Charles Felix in 1849. His first act was to sign a peace treaty with Austria. The King's great loves were the hunt and his armed forces. He maintained his father's liberal constitution and, realizing his own limitations at statecraft, looked for able public servants to manage the affairs of the Kingdom. One of his most able advisors was Camillo Benso, Count Cavour, who rose to become his First Minister.

The failures of the revolutionary movements of 1848 demonstrated that ideas alone do not forge nations. Throughout the Italian peninsula, especially in the North, there had developed a theory of national unification, or Risorgimento. But this movement for unity had many aspects and lacked central leadership. Giuseppe Mazzini's ideas instilled fear in the capitals of most of the states of Italy, including Turin. Some wished Pope Pius IX would lead a movement for a national confederation with the Papacy as its head. Others believed that King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies, another powerful Italian ruler, should lead the movement. Another faction, including Cavour, believed that the Risorgimento should be led by the House of Savoy to ensure the future institutional makeup of the nation as a conservative and constitutional monarchy. There was no consensus and little leadership from any part that was connected to the other. King Victor Emmanuel desired to redraw his nation in the concert of Europe. And so, he allied himself with Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire when the Russians invaded the Crimean Peninsula, commencing the Crimean War. Fortuitously, the war did not expand beyond the Crimea and it was short lived. The Piedmontese forces acted bravely under fire. Count Cavour earned his place at the Congress of Paris that concluded the war and it was there that he tested the idea of a unified Italy with French help. The cautious King, with his own father's experience in mind, would not challenge the Austrian Empire without the support of another superpower. The idealist Mazzini had roundly declared that "L'Italia fara da se!" But the King of Piedmont was too much a pragmatist to think that the Austrians would give up Lombardy without a fight. |

|

Cavour, with the King's grudging concurrence, arranged a secret meeting at the resort town of Plombières in 1858 with the French Emperor, Napoleon III where they concluded the Plombières Compact. By its terms, Piedmont would stage an insurrection in Italian lands. When the Austrians moved to quell the disturbance, Victor Emmanuel would march to defend the Italians and the French would back up the Piedmontese as their allies. The price was not insignificant: Piedmont would cede Nice and Savoy to France in perpetuity. The icing on the (wedding) cake was that Victor Emmanuel's young daughter, Princess Clothilde, would marry Napoleon III's rakish older cousin, Prince Jerome Bonaparte, known as "Plon-Plon" due to his shape and joie de vivre.

The war came in 1859 and it ended almost as soon as it began. The unmanageable carnage at the Battles of Solferino and Magenta was so appalling that it led to the formation of the International Red Cross. The mutilated and unrecognized corpses of tens of thousands of soldiers so horrified Napoleon III and the young Emperor Franz-Josef that they met to conclude a peace. As the Austrians were in retreat, Napoleon made a hurried peace with Franz-Josef, whom he came to respect for his courage and dignity. The French shied away from finishing the work of unity and, without consulting the King, permitted the annexation - after a referendum - of Lombardy; but the Austrians maintained the Trentino, Alto Adige and Venice. Cavour reigned in protest and Victor Emmanuel accepted the peace. Savoy and Nice were transferred to France, without the concurrence of its populations. Clothilde was dispatched to Paris and an unhappy life with Plon Plon. Cavour thereafter returned to the Cabinet and secretly fomented insurrections in Parma and Modena, as well as Tuscany, to destabilize the Habsburg and Bourbon-Parma rulers so as to trigger Piedmontese intervention. A Kingdom of North Italy was established from the Swiss and French borders to the Papal States and bounded to the northeast by Austria. Victor Emmanuel II became its King and the capital was moved to Florence. |