American Delegation of Savoy Orders

|

Despite gloomy economic prospects in the short term, Italy today must be considered one of the most civilized countries of the world. Outsiders are always disdainful of the corruption and political chaos, and almost a century and a half after the Risorgimento, Italy is indeed "ancora una federazione" with little faith in central government. However, this seems to suit them quite well. The standards of living in northern Italy are among the highest in the world. As for the long-standing differences between north and south, these are paralleled by equally strong economic contrasts in other developed nations, notably Germany at the moment, and even America. In business, Italians are flexible and inventive, and despite a cherished image of dilettantism and the siesta, can work extremely hard when they want to. When they make money, they do so in order to spend it, and less to compute it as a success symbol like here. This is a nice set of compliments, but Italians are perhaps less admired at fighting wars and when Italy joined the Axis Powers in 1940, Churchill said, "That's only fair, we had them the last time." Even the military dress uniforms one encounters in the streets look operatic and are hard to take seriously as a carapace of martial ardor. This equivocal reputation is reinforced by their poor performance in World War II, when they fought without conviction under poor leadership for a regime in which they had lost confidence. Mussolini they treated like an occupying power in the tradition of previous overlords like the Spanish, the Hapsburgs, or the French, going along with them as long as they were useful, then dumping them when diminishing returns appeared and extramural political situations changed. Unfortunately, from a military point of view, all this was overshadowed Italy's far more creditable performance in the First World War. In this country most schoolchildren, even those of Italian descent, are hardly aware that Italy was involved at all and the Great War is part of a large, blank area of Italian history between the Risorgimento and Fascism.

|

For those who know a bit more about it, the following perceptions are still commonplace, none of them very flattering.

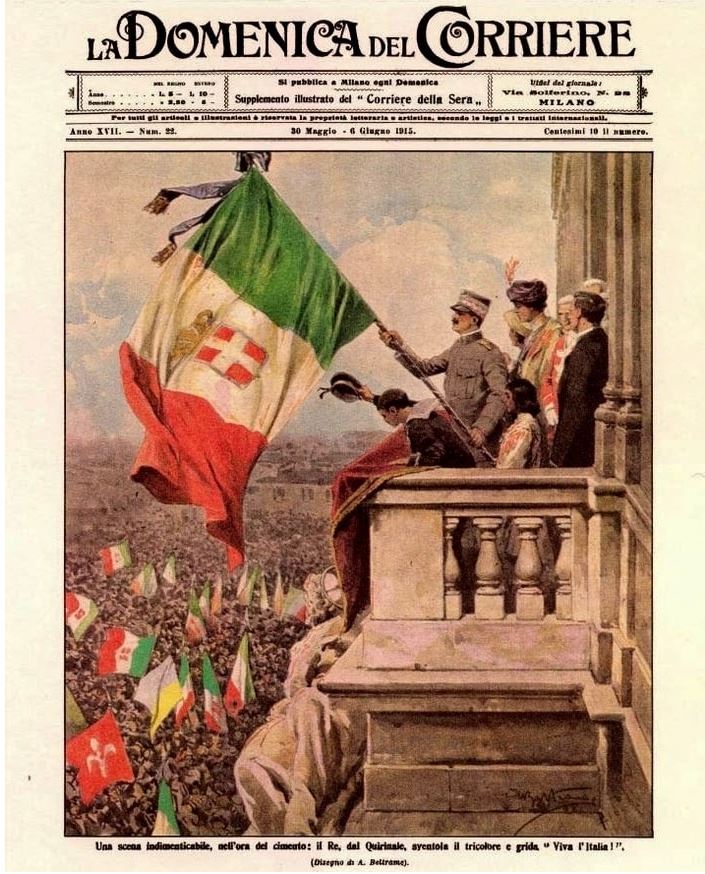

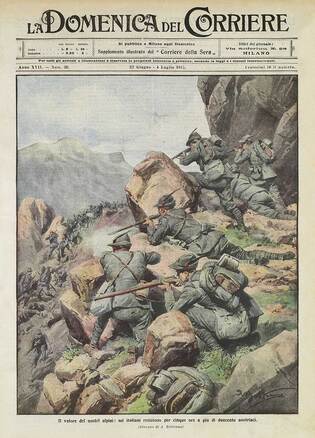

1) That Italy, having for years been part of the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany, treacherously changed sides out of territorial greed selling herself to the highest bidder and joining the Entente (Britain, France and Russia) in 1915. 2) That the Italians fought badly and were badly led, and never believed in the war until jolted into some sense of urgency after their defeat at Caporetto in 1917. After that they only won by default, since the opposition, chiefly Austria Hungary, was just as incompetent and in the end, simply packed up and went home. 3) That the whole Italian war was a muddled discreditable episode, which deeply divided an already divided nation. This led to fascism, which offered a quick fix to the ensuing political chaos. 4) That the war was in any case only a sideshow compared with the really decisive theatre, the Western Front. As will be seen, there is an element of truth in some of the above, but in this lecture my goal is to see Italy's War in a more positive light to vindicate her performance and present a fairer and more accurate picture of her role. In accordance with my brief, 1 will highlight the contribution of the Savoy family and indulging my own particular interests, will focus as much on military history, especially tactics, as on the social, political and economic background. |

|

I want to try and get across the following points:

1) That Italy, proportionate to her population and length of participation (three years as opposed to four for the other great powers) incurred as high losses and fought just as tenaciously as anybody. Total casualties, in fact, were about two million and war deaths approached 600,000. 2) Wars are not always fought for high ideals. Italy's motives for entry may have been based on territorial gain, but such ambitions were common to other belligerents. 3) Though the political leadership was lackluster, and though the Italian army had many faults, its military deficiencies were only different in degree from other countries. They were not different in kind. This is unsurprising since all the warring nations were forced to cope with the unprecedented problems of war on an unprecedented scale, in which the power of modem weaponry made defending easier than to attack. I don't want to say that World War I was a good thing. It is the single most disastrous event of the 20th century and was a direct cause of the militarization of Italian and German politics which lead to World War II, but the Kaiser's Germany was well worth defeating. Life under a victorious Germany would have been pretty unpleasant and to Germany's defeat, the Italians made a sound contribution. The Savoy family, notably the King, V.E. III and his cousins the Duca d' Aosta and the Duca degli Abruzzi, played a significant part and were thought to have done so at the time, not merely acting as figureheads. Aosta commanded the Third army on the Isonzo and Piave fronts for the whole war and Abruzzi was Naval Commander in Chief in the Adriatic until 1917. The King spent most of the war with his troops at the front. His role was perhaps more passive than it might have been given his potential clout as titular Commander in Chief, but his presence was supportive and stabilizing and he never wavered in his determination to win. |

|

As I have shown, Italy entered the war more divided than the other combatants and less united by patriotic fervor. Indeed the Treaty of London was the result of a virtual conspiracy between the King, the Prime Minister Salandra and the Foreign Minister Sonnino. The army were kept in the dark, and when informed, were pretty surprised having expected to be fighting with Austria instead of against her. This showed the serious lack of cohesion in a country where the concept of nationhood was still only skin deep.

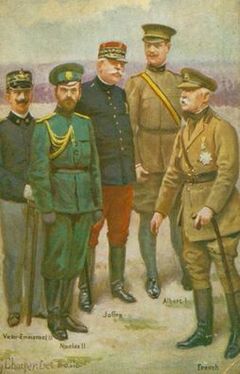

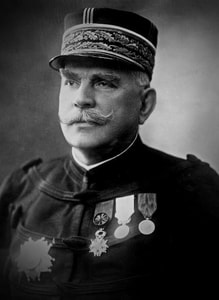

The Italian Commander in Chief, Count Luigi Cadorna (for better or for worse) is the outstanding figure of Italy's War, comparable in importance to Douglas Haig in the British Army, and to Ludendorff in the German. He came from an old Piedmontese family, the state that had unified Italy and had by far the best army with a high tradition of professionalism. His father Raffaelle had put the coping stone on the Risorgimento by winning the Battle of Porta Pia in Rome in 1870, forcing the French to withdraw and leaving the Papacy isolated in a secular state. Cadorna was a fine organizer and trainer of men and like Haig, stubborn in his conviction of victory, but he was an autocrat with little confidence in his troops and out of touch. The old racist chestnut, L'Africa comincia a Napoli, gives an idea of his attitude, since large parts of his army were from the south. Since he deeply mistrusted politicians, Africa probably began a bit further north in the Montecitorio Palace in Rome, the seat of the Italian parliament. Just as Cadorna's government had failed to tell him which side they wanted him to fight on, so Cadorna got his own back by running the war on his own. Attempts by politicians to get rid of him when he failed to produce decisive results were ruthlessly repressed, helped by his well- developed persecution complex hypersensitive to any threat. Such distrust of politicians was not confined to Italy. Haig in Britain and Joffre, the French Commander in Chief, both distrusted civilians or frocks (so-called because they wore frock coats), and for long succeeded in keeping them at bay. The frocks on their part, unlike Churchill in World War II, lacked confidence in military matters and were happy to let the generals get on with it. When increasing casualties appeared to be leading nowhere, Joffre was kicked upstairs in 1916, but Haig survived all attempts to replace him, because no one could think of anybody better. The two military stars in Germany, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, in an ominous precedent turned the country into a military dictatorship. |

|

It is important to remember that in this kind of warfare, however skillfully conducted, casualties were bound to be high. This was recognized and accepted by all sides, though less understood on the home front. The trick was to prevent casualties being prohibitive, but this they were bound to be if infantry assaulted with insufficient protective fire. Protection was needed to enable troops even to reach the trenches let alone capture them, so where was it to come from? In the absence of air cover available in the next war, the best protection came from artillery, the key Great War weapon, even more than the machine gun, and much more than newer style weapons like the tank. This protection typically took the form of:

1) counter-battery work, i.e., eliminating enemy artillery which could be lethal against troops in the open 2) bombardment of enemy trenches which kept defenders in their dugouts. From these they would hopefully not have time to emerge between the lifting of the bombardment and the arrival of the assault 3) The creeping, barrage, a protective curtain of fire, which ran ahead of the infantry and lifted when they reached the enemy trenches 4) The surprise factor. A long bombardment might be destructive but would alert the enemy. So later in the war, short but very intense bombardments became the fashion. |

All this obviously required infantry and artillery to be synchronized, and for artillery to be accurate and with enough weight of shell to destroy targets. This meant more heavy guns which were less mobile but more destructive than the lighter calibers. Once the first line of trenches was taken, further lines might need to be neutralized before a breakthrough beyond the defense zone. The best tactics were to stop, consolidate gains, bring artillery forward, then regroup to beat off counter-attacks prior to attempting the next leap forward. This concept, called "Bite and hold" was only consistently adopted late in the war. Before that, the generals were usually too impatient to adopt such tactics, and flush with offensive spirit, always wanted to go too far too fast, failing to stop and consolidate initial gains. This meant increased vulnerability to counter-attack since the further the advance, the more extended became lines of communication and control, and the greater the exhaustion of the troops. The further men advanced beyond their own artillery, the less accurate their own protective fire and the greater their vulnerability to the guns of the enemy. If one unit advanced ahead of another as they were often encouraged to do, its flanks became exposed especially to enemy machine guns. Failure to address all these problems were to blunt many an attack on the Western Front as well as in Italy. Such problems were only really mastered by the Germans late in 1917 and by the Allies in 1918. Only when artillery became accurate enough to be a precision weapon could it provide adequate protection to an attack, and then only when the attackers learned to stop and consolidate before each bound, rather than sticking their necks out in the hope of a Napoleonic style breakthrough.

|

|

After this slightly complicated crash course in the problems of trench warfare, let's turn to the problems of the Italian Front, not forgetting that many of them were of the same kind as elsewhere, especially on the Western Front in France. In the wide open spaces of the Eastern Front against Russia, fighting was less static and the advances made were far greater territorially. The biggest problem in Italy was that although the Austrians were outnumbered two to one by the Italians, the ground held by the Austrians was mountainous and so highly defensible, and long distrust of Italy had encouraged them to fortify it carefully. On the Western Front, Germany occupied French soil, so the French had to do the attacking. Obviously since Italy wanted to redeem territory from Austria, going on the defensive was out of the question. The Austrians, much more vitally engaged against the Russians in the north, were quite content to defend since this could be done with fewer troops. Admittedly their armies were flawed by ethnic and linguistic divisions, they had lost the flower of their officers in early battles against Russia, and to attack successfully they usually needed German help. In defense, however, they could manage perfectly well on their own, and even Ludendorff agreed that they fought best against Italy whom as a former ally, they regarded as a traitor. |

|

|

|

|

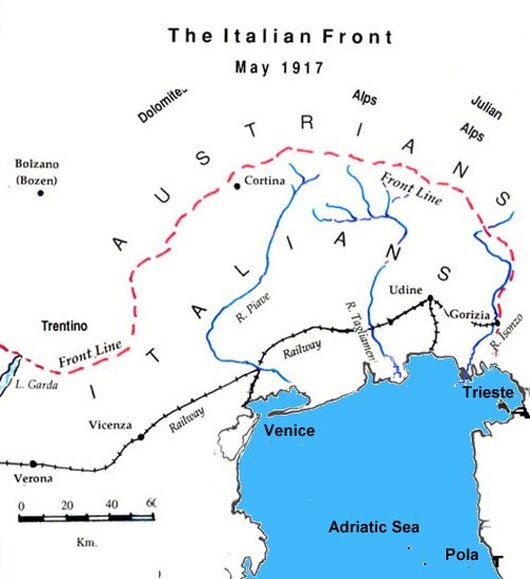

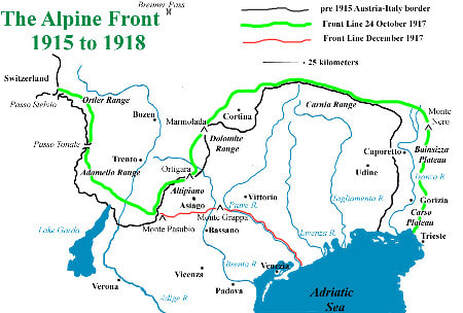

The Italians had two options: to attack in the Trentino aiming for the Brenner Pass and the Tyrol or to attack on the northeastern frontier along the Isonzo Valley and across the upland plateaus of the Carso and the Bainsizza. The Trentino was highly defensible, the Isonzo a bit more open. It appealed to Cadorna since, like all generals on both sides, he wanted a quick and decisive victory and a breakthrough here provided the shortest route to Vienna. However, the terrain was inhospitable in the extreme, and the plateaus a stony wilderness, where artillery created its own shrapnel with showers of rock splinters from detonating shells. In hindsight, in fact, the idea of a quick breakthrough seems a fantasy. On the economic front, Italy's industrial base had greatly strengthened during the early 20th century and was to grow exponentially during the war. However, she was still way behind the great powers of Northern Europe and to start with she lacked heavy and medium artillery, machine guns, and even ammunition. Such problems were common to all the belligerents early on, especially shell shortages since everyone thought the war would be short. By 1916 they had been largely overcome, but Italy took longer since her weaker industrial base made her more dependent on imports.

|

|

With the Isonzo appearing to offer the best chance of success, Cadorna spent the first two years of the war launching as many as 11 offensives there but Cadorna, following the somewhat dismal pattern of the Western Front, never gained any thing decisive or looked like making a breakthrough. Like Verdun, the Somme, and Passchendaele, the Battles of the Isonzo were battles of attrition, killing lots of Austrians but also lots of Italians. The British and French, especially after the Somme in 1916, made concerted efforts to address the problems of attack. The trouble that the Germans countered by developing greater defense in depth. Their front lines were now thinly manned so that they acted like a shock absorber, enticing attackers forward into the defense zone where they would be zapped by counter attacks or by strong points dotted about. So both sides remained evenly matched. On the Italian front, neither side showed as much sophistication but the Austrians probably learned more from German defense methods than Cadorna from his Allies' improved tactics in attack. Indeed his learning curve was shallower than most and despite flashes of imagination among his subordinates, he himself never really abandoned the habit of throwing men into frontal attacks insufficiently protected by artillery. A typical scenario might be as follows: a preliminary bombardment not intense or accurate enough to destroy barbed wire, trenches or enemy artillery and stopping too soon alerting the enemy to a coming assault. Once the front line was gained, a straggling further advance would expose attackers to counterattacks, especially on the flanks. Reserves might be held too far back, and artillery not brought up fast enough to cover a further advance. The creeping barrage was little used.

These mistakes were made by all the Allies, but the effective coordination between infantry and artillery achieved in the last months of the war were never aspired to in Italy, as indeed British and French observers were to point out. In the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo in 1916, the Italian artillery was unusually heavy and accurate resulting in the capture of Gorizia. This was hailed as a victory, but as the King pointed out earlier, Gorizia had no strategic value and the end result was an Austrian retreat to even stronger defenses than before. The problem with such attrition tactics was that while they wore down the enemy, they wore down the attackers also, whose morale was undermined by lack of results. This made them vulnerable when the attackers became the attacked, as at Caporetto in 1917 or with the British in 1918, when their line was pierced in late March by the German Spring offensive. These were among the most spectacular reverses of the war and it is symptomatic that they should have been inflicted by an enemy in areas where the enemy had previously been on the defensive. In Italy the debilitating effects of attrition were exacerbated by Cadorna's command style. He believed his army were an unruly lot who could only be controlled by Draconian methods. Exemplary punishment (even decimation) was demanded against units that had underperformed, and he sacked more generals than any other Commander in Chief. This killed initiative, and subordinates became more concerned to keep their jobs than to beat the enemy. This sounds bad, but in any vastly expanded army like all those of World War I, there were bound to be a lot of over-promoted senior officers who need weeding out, Giolitti, the great Italian liberal politician observed, "the generals are worth little. They came up from the ranks at a time when families sent their most stupid sons into the army because they did not know what to do with them." In France Joffre was also a great sacker of generals in the war's opening months and Haig's army was also pretty hierarchical. In the German army by contrast, within the General Staff at lest, the circulation of ideas was encouraged and even junior officers were given a hearing. |

|

Cadorna's other problem was that he remained out of touch with his men, isolated in his headquarters at Udine. Obviously in coordinating the immense armies of World War I, no general could lead from the front and the static nature of the war discouraged mobility. But with Cadorna the situation was exacerbated by his staff, who were small and subservient, and prone to issue orders without following up to see if they were carried out. Paradoxically this meant that however autocratic, Cadorna had less control over his subordinates who proceeded off their own bat or picked what option they liked from orders that were often ambiguous. At first Cadorna's lack of progress on the Isonzo was taken on the chin by the politicians in Rome content to let the army run the show. As I mentioned, this was a typical World War I scenario. If Cadorna didn't deliver decisive results nor did the French or British, and like Haig and Joffre, he impressed by his granite self-confidence, a quality not to be underestimated and indeed essential for keeping troops with their noses to the grindstone. The first serious signs of political discontent appeared when the Austrians, under General Conrad, attacked in the Trentino in 1916. Conrad hated Italians and called this a punishment expedition. It was quite successful at first because Austrian artillery was heavy and accurate. For the Italians, the battleground, centered on the Asiago plateau, was dangerous since close to the edge of the Alpine foothills. If they were pushed off them, the enemy could flood into the north Italian plain. The Italians had noted Austrian preparations but not taken them seriously. They also made mistakes common to all armies who usually did the attacking keeping their troops in offensive rather than in defensive dispositions, neglecting to provide defense in depth, keeping too many men packed in the front lines, and their artillery too far forward. So the line was brittle without much elasticity. However, initial Austrian success was not kept up. In defensible, hilly terrain, the offensive ran out of steam against tenacious resistance. Using a good internal rail system, Italian reinforcements were rushed from the Isonzo. Eventually the Austrians fell back on strong defenses since troops had to be withdrawn to the Russian front to counter an offensive by General Brusilov near the Romanian border. This exceptionally well-prepared Russian attack had been timed to coordinate with the British Somme offensive in France. It helped the Italians as well obviously, but the Entente had yet to develop a coordinated strategy with Italy, who continued to fight a parallel war on her own. Periodic Italian -appeals were made for Allied help, and were especially well received by the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, who never ceased to look for an alternative to the Western Front. However, apart from the loan of a few guns, nothing much happened, partly out of pressure from Allied "Westerners" opposed to any diversion from the Western Front and because the Italians feared too much dependence on their allies, especially Cadorna who wanted no challenge to his authority.

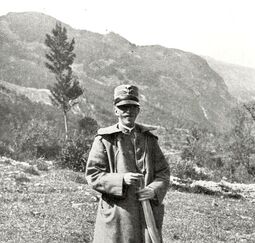

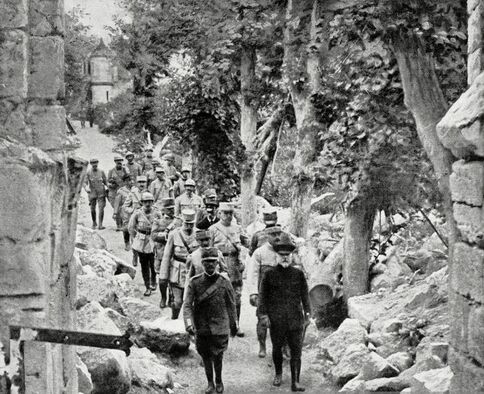

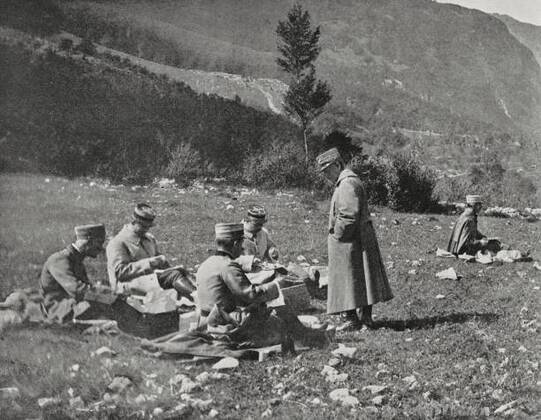

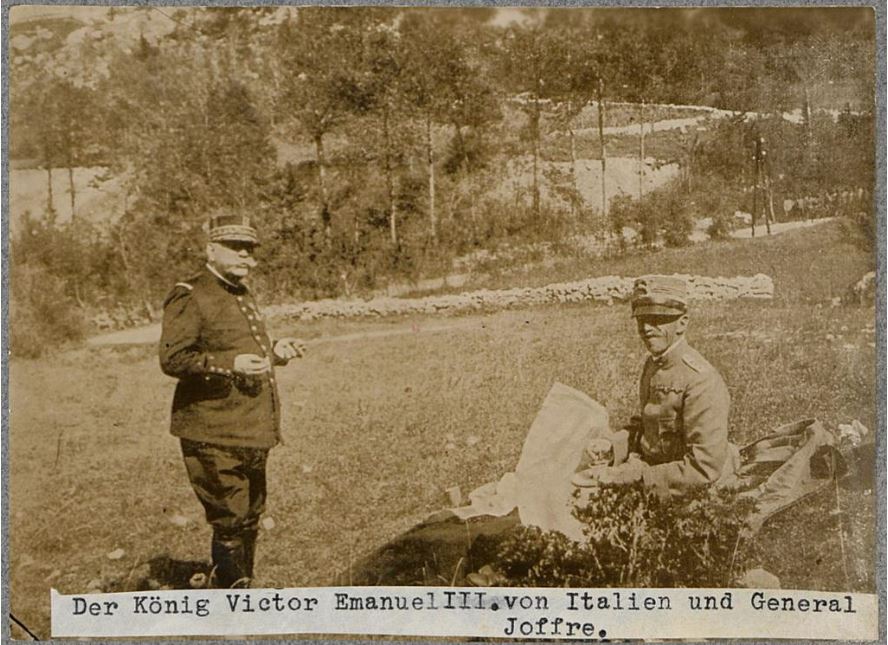

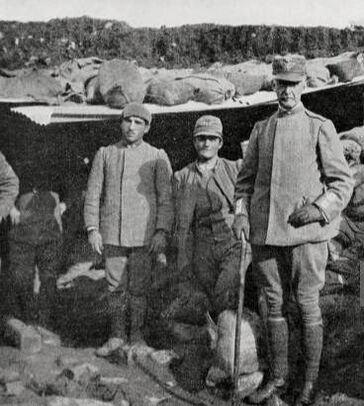

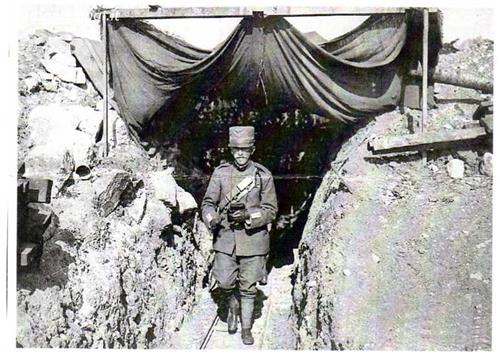

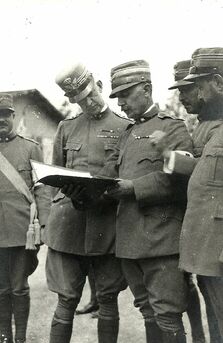

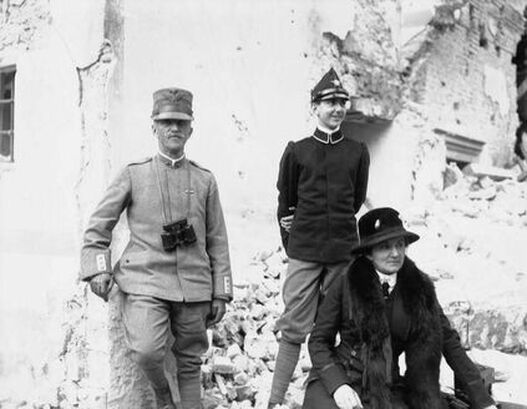

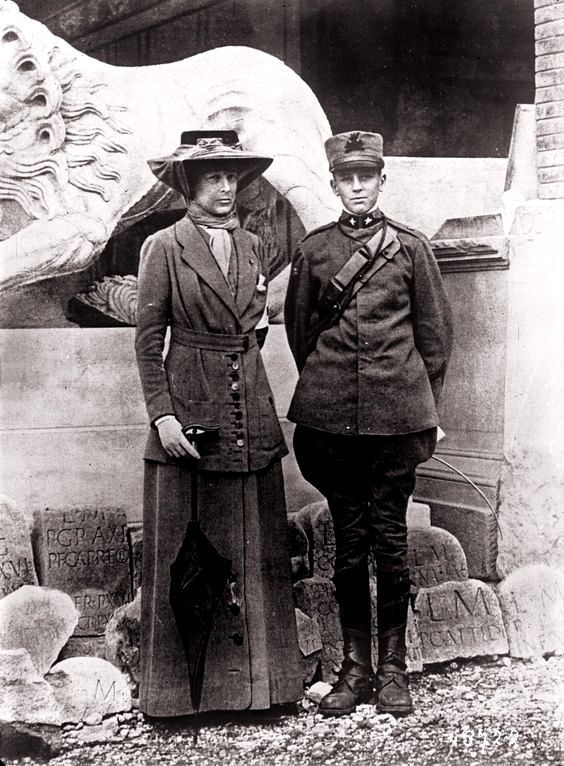

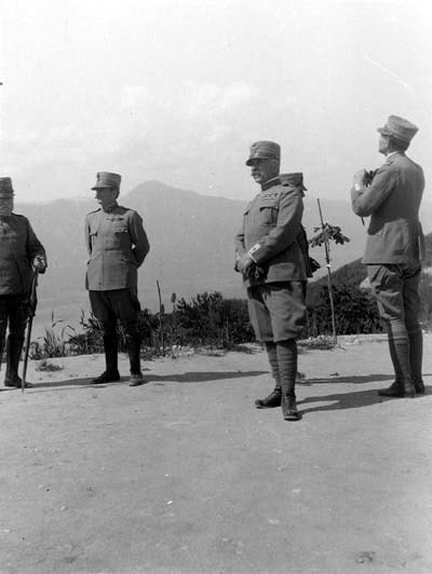

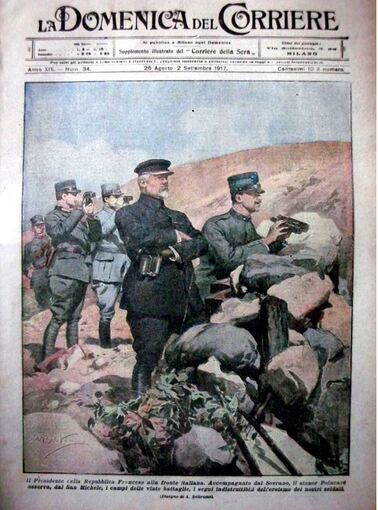

The Austrian offensive caused considerable alarm and led to a change of government but Cadorna, politically a master of defense, survived. Just as Haig enjoyed the constant support of King George V (he had married a lady-in-waiting to the Queen) so King VE III was a loyal supporter of Cadorna. The King, spending most of his war at the front and occasionally under fire, was a familiar figure constantly touring the lines with his camera. As titular Commander in Chief, and a scion of the Piedmontese military caste, he felt uncomfortable with politicians, and like many a Roman emperor, preferred the life of the camp, where choices were simpler and the job to be done clear cut. He preferred to avoid confrontation but could perhaps have done more to forge better relations between Rome and the generals. He lived more like a regimental officer than a Commander in Chief and Colonel Repington, military correspondent of the London Times, gives a sympathetic picture of his unregal existence. "I had a private audience with the King at his villa at Udine. It was a humble residence with a small garden. There were three or four officers about, and a sentry but I saw no other guard. I was shown up at one to his bedroom in which he appears to receive especially favored guests. It was the humblest kind of room imaginable. There was just a low camp bed with a soldier's blanket over it. A small, hard table and two small, hard chairs made up the rest. The King met me at the door; he is even shorter than I imagined but was very cordial and spoke volubly and well in English. |

|

|

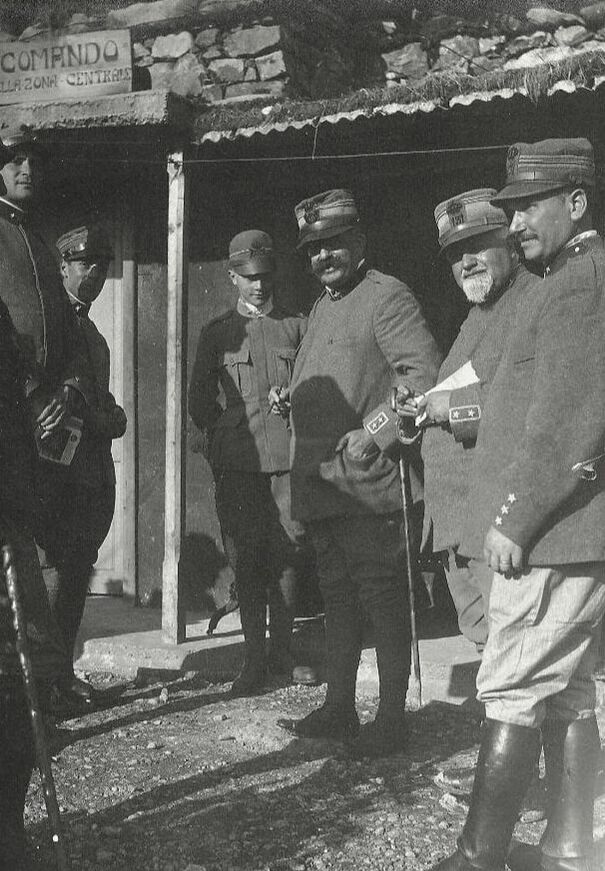

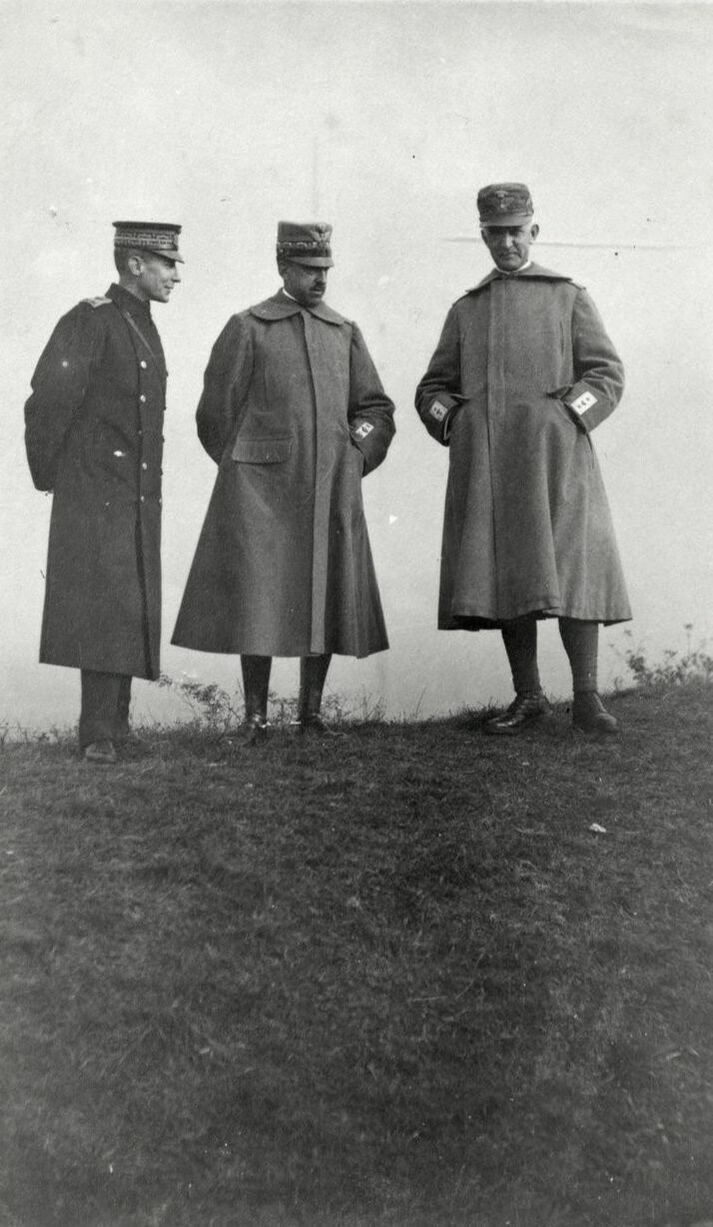

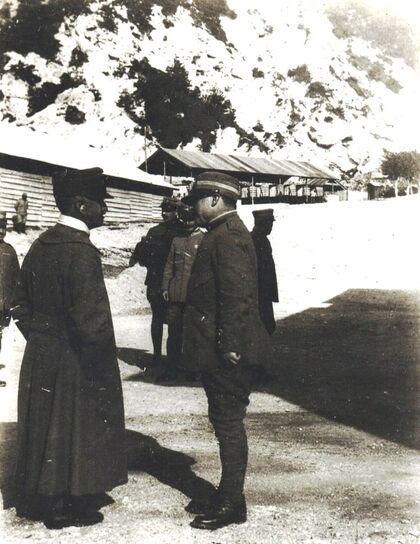

The second most prominent of the Savoy line in the war was the Duca d' Aosta, the King's cousin and Commander of the III army. He was tall and imposing, which upstaged the King, and the two never really got on. Aosta was a very competent commander, famed for his clear orders, but did as he was told, both tactically and in support of the harsh discipline demanded by Cadorna. Nevertheless, he had good rapport with his men, to whom he seemed a glamorous figure, but who were sometimes rather perplexed by his d'Annunzian rhetoric. As a natural looking hero, he was a useful propaganda image but in the view of the diarist Colonel Gatti, he always maintained a certain princely detachment. Two minor royal figures were Aosta's younger brother, the Count of Turin inspector general of cavalry, and the Duke of Genoa, the King's uncle and deputy in Rome.

In many ways the most sympathetic of the Royals was the Duca degli Abruzzi, another brother of Aosta, who commanded the Adriatic fleet from 1915-17. Abruzzi was famous as an explorer and also for his unhappy love affair with an American heiress, Catherine Elkins, which ended possibly because the lady's father was too much of a robber baron for the Royal family's taste. The Adriatic Sea was the center of Italy's naval war. Both sides had modern dreadnought battleships, though far fewer than Britain or Germany, but were reluctant to risk them in a major battle since unlike losses in men, ship losses could not be quickly replaced. Heavy ships were also vulnerable to mines and torpedoes in the narrow confines of the Adriatic, so they spent much of the war in harbor, a potential rather than an active threat. There was a French fleet at Corfu and some older British battleships at Taranto, but allied cooperation was impeded by reluctance to accept an admiralissimo of another nationality. Some cruiser and destroyer actions did take place, notably the Battle of the Otranto Straits. The Germans had developed a highly successful submarine fleet which in the Mediterranean took great toll of shipping to and from India, the Far East, and Australia via the Suez Canal. Some of these U-boats operated from Austrian bases on the East Adriatic coast, and to prevent their escape into the Mediterranean, the British deployed the so-called Otranto barrage, a line of drifters protected by minefields and armed with anti-submarine nets. This was ineffective, but the Austrians never realized it. Under Captain Horthy, the future regent of Hungary, they successfully attacked the drifters. On their voyage home an Allied force caught up with them but withdrew in the face of Austrian reinforcements, so the battle was a draw. Both sides did better in hit-and-run attacks with small boats, M.T.B's and human torpedoes, especially the Italians who achieved spectacular success sinking Austrian Battleships, a field in which they were to prove equally skillful in World War H. Perhaps the most effective Italian naval operation, presided over by the Duke, was the Allied evacuation of the defeated Serbian army from Albania, after it had been routed and driven south by an Austro-German invasion. As the British admiral Thursbey remarked, "with the scratch pack we have to deal with and with ships and material from three different nations. I don't think anyone but the Duke could have done it. In addition to being able and energetic, his position enables him to do more than any ordinary Admiral could do." Abruzzi had the reputation of being more aggressive than the chief of naval staff Thaon di Revel, but attempts at combined operations with the army against Trieste never materialized owing; to poor relations between the services and fear of mines and torpedoes in shallow coastal waters. |

|

In Italy Cadorna kept plugging away on the Isonzo. In October 1917, a better organized attack with heavier and more concentrated artillery resulted in more gains than usual in the southern sector. Again nothing was achieved that looked like a breakthrough and progress on the Bainsizza plateau, though successful by the modest standards prevailing, left the Italians in control of a waterless and provisionless wilderness, and the advance petered out. Like Nivelle's offensive in France, the battle brought the Italians near the end of their tether and disaffection increased. The Austrians, however, took fright. The aged Franz Joseph had been succeeded by the less stalwart emperor Karl, who had been trying to secure a separate peace. Another of these offensives he said and we are finished. He probably exaggerated but Germany decided to act and bolstered their ally by sending seven good divisions to the Isonzo, including mountain troops. The idea was that the best defense was attack, but they did not expect to achieve any spectacular gains. In fact they brought off one of the great victories of the war, Caporetto.

On the Italian side, the situation prior to the battle was as follows: On the Southern Isonzo lay the III army under the redoubtable Duca d' Aosta. To the north lay the 11 army under General Luigi Capello, an imaginative commander, sometimes critical of Cadorna, and very offensive minded. There was plenty of evidence for a coming attack, but Cadorna failed to take it seriously. If it came, he expected it to happen in the south, not where it actually happened, against Capello in the north, where Cadorna thought the mountains precluded heavy operations. So without reinforcing Capello, he went on leave. This can happen and Rommell, in the next war, went on leave before D-day, but Capello himself fell ill and so was in and out of the fight. His troops were left badly disposed. Many of them were east of the river, but the Austrians still held two bridgeheads, and so had access to both banks, where they could range up and down behind the Italians. Typical of a general used to the offensive, Capello wanted to be able to attack as well as defend. So he neglected defense in depth, and packed too many of his men in the front line. When the Allies were successfully attacked by Germany in their 1918 Spring Offensive, General Gough, the British 5th Army Commander, made the same mistake with equally dire results., So the old-fashioned spirit of the offensive still persisted in all armies. Against Germans, such lack of focus was asking for trouble, and the Italians compounded their error by keeping their reserves too far back in a cautious attempt to cover all bases. On the other side, the Germans brought new tactics to bear, which they had been developing on the Russian Front, in particular the use of infiltration of troops. Under this system small heavily armed elite units were sent forward prior to the main attack to penetrate weak spots, bypassing strong points, and keeping up a relentless advance. This surprised and confused their opponents, opening up gaps through which crack assault divisions would then pass. At Caporetto a modified version of these tactics was applied. Standard mountain warfare doctrine dictated that strong points on the peaks dominating the battlefield should be neutralized first. At Caporetto the assault divisions instead penetrated the valleys leading to behind the Italian lines, while infiltrators took care of the strong points on the heights. In the latter, the young Erwin Rommel was particularly successful, relying on surprise, so that large bodies of troops surrendered to him without loss, though he was grossly outnumbered. |

|

The preliminary bombardment was also up to the latest standards, intense and accurate and directed not only against the front lines and artillery, but against lines of communication. Gas shells were part of the mix, against which Italian masks were ineffective. The traditionally poor cooperation between infantry and artillery deprived Capello of support and many of his front line troops were of poor quality and put there to knock them into shape. The results of all this were fairly predictable. Capello's army collapsed in rout, just like the British 5th army the following year. The Italians streamed back in retreat and ominously, lost more men through capture and desertion than through battle casualties. A celebrated account of the retreat is in Hemingway's Farewell to Arms, where he describes battle police summarily executing deserters, a very Cardornian scenario. In fact Hemingway was not present at Caporetto, but working as a reporter in Kansas City and didn't reach Italy until the following year, where he drove an ambulance. However, the brooding sense of disaster is still wonderfully conveyed. Like in their later Spring Offensive, the Germans never expected to be so successful, and inevitably the advance slowed up as communications became clogged and ill fed Austrians stopped to plunder. This allowed the Duca d' Aosta's III army, which had not born the brunt of the attack, to be skillfully and successfully withdrawn.

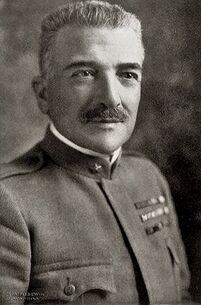

Nevertheless, the line of the first major river, the Tagliamento, could not be held. The retreat continued until the Piave, 30 miles from Venice. Having advanced so far and fast, the Austro-Germans were exhausted. The Italians, despite great losses of men and materials, were galvanized into a stubborn defense and the line held. However devastating at the time Caporetto, like the German Spring Offensive, was not a decisive victory in the long term. The Italians now had their backs to the wall. If the Piave was breached the whole of northern Italy was at risk. So the war, which thus far had deepened the clefts in Italian society, leading to serious rids in Turin earlier in the year, at last became generally popular. The government fell and the new Prime Minister, Orlando, like Lloyd George in Britain and Clemenceau in France, was determined to prevail. Italian industry, vastly expanded, and quite well run in a partnership between the public and private sectors, soon replaced all the losses at Caporetto from domestic resources. The Piave line was shorter than the Isonzo, and closer to the Trentino front shortening communications. The river was dry in summer, but in the fall and winter rains swelled into a formidable barrier. The German troops were soon withdrawn being needed for the far more decisive battles on the Western Front, and as far as Germany was concerned, Italy could be left on ice. The Austrian army was still formidable but poorly provisioned and ethnic differences were beginning to widen as nationalist divisions within the Empire crystallized. Cadorna, in an attempt to cover up his purely military errors, blamed his defeat on Bolsheviks and other subversives, which went down badly. The government, the King, and the Allies lost confidence and he was replaced by General Armando Diaz. The name of Diaz is familiar to every tourist killing time while waiting for the local museum to open since his victory dispatch is engraved on the walls of every municipal loggia A. J. P. Taylor said of Diaz, "No better a general than Cadorna but at least different." He was certainly not one of the great captains of history, but got on much better with politicians, and was more accessible to his colleagues and troops. Like Petain in France, he modified the Draconian discipline, improved food and leave, and even instituted a free life insurance scheme. Like the French, he was prepared to defend, but doubted his army's offensive capacity, which needed time to recover, and so steadfastly resisted Allied pressure to attack. The King at this time was at his best, and in a famous audience at Peschiera, he affirmed Italy's determination to prevail. From now on he, the government, and the army succeeded in working together more closely. The Duca d' Aosta had been considered a serious contender for Cadorna's post, especially by the Allies, but the King vetoed it. Perhaps he feared that if Italy lost the war, Aosta would have to carry the can, and the monarchy be endangered. Another reason my have been that he didn't want the Duke to develop into a more formidable public personality than he already was. |

|

Caporetto thoroughly alarmed the Allies. They realized they had to get their act together on inter-allied cooperation, so a supreme war council was established at Versailles to which Cadorna was sent as Italy's representative. The Allies also sent 11 British and French divisions to Italy. These contingents were commanded by Generals Fayolle (French) and Plumer (British). Plumer, the blimpish looking commander of the 2nd army in the Western Front, was one of the better generals of the war and known for his meticulous preparations and staff work. His greatest exploit was the mining and capture of Messines Ridge near Ypres. Plumer was also an effective diplomat, and unlike some of his colleagues, never showed contempt for a defeated ally. The British, at least, were delighted to be fighting in Italy and away from the mud of Flanders but were not trained or equipped for mountain warfare. At first the Allied contingents stayed in reserve, to the annoyance of their hosts, but sensibly not wanting to be indiscriminately thrown into plug a weak spot and wiped out. After the line consolidated they deployed around the Montello sector in the Middle Piave. They found the Italians still technically backward. In defense, trenches were too shallow, machine guns too exposed, and too many men were in the front line. There was not enough strength in depth, and no creeping barrage. They were disinclined, as Plumer said, to go in for scientific accuracy in artillery, and had a tendency to down tools over lunch. Training schools were established to impart the latest ideas but not well attended. Most important however, the Allied presence, without being decisive, was good for morale, and showed that at last the Entente Powers were pulling their oars in the same boat.

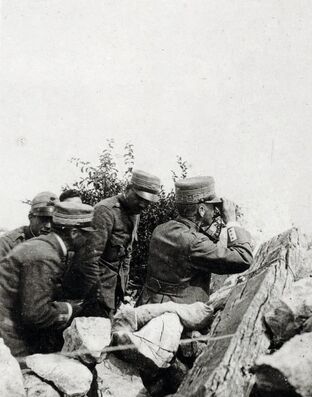

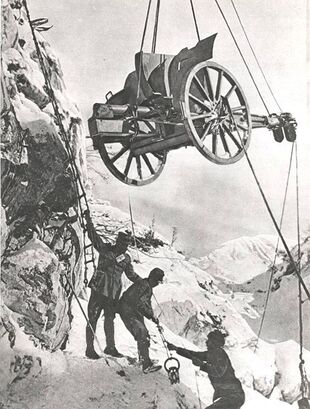

At Asiago, coincident offensives by the Austrians alone were parried but fighting was particularly contentious in the area further east, around the Grappa Massif above Bassano. The Grappa had always been recognized as a decisive spot since it guarded the upper valleys of the Brenta and the Piave leading down to the plains. A breakthrough here would have threatened the Piave Line in the rear, in an encircling pincer movement. In this precipitous region in late 1917, the Italian Alpini successfully held off the best German and Austrian mountain troops. Mountain combat was tough but supplies and munitions were effectively carried to remote ridges and peaks by rudimentary cable cars. Some defensive positions had to be tunneled out of the ice. The Italians have always been brilliant engineers and their military roadways were much admired by visitors. To many places, however, equipment could only be conveyed by mule, or Shank's pony. Hauling artillery up into remote positions was time consuming and many guns are said to be still there to this day. Fighting at altitudes above 5000 feet was also physically taxing and could cause permanent injury to the lungs. |

|

Around the Grappa, winter conditions soon brought the campaign to an end, and the situation on the Piave also calmed down. The next major battle took place at Asiago on the Trentino Front. Early 'in 1918 Plumer and Fayolle were recalled to France. Plumer's place was taken by the Earl of Cavan, who commanded a reduced force after several divisions had been returned in response to the German Spring offensive. The Allies had themselves planned an offensive at& but were pre-empted in June by the Austrians, who also launched a supporting attack on the Piave. This was a mistake; they should have concentrated on one or the other front, especially since their army was in decline. Failure to achieve anything decisive, as previously with the Italians, had sapped morale, and there was a shortage of all kinds of equipment and food. Some progress was made, especially at Asiago, but ground was soon recovered. Ironically Cadoma's propensity to sack his generals appears to have been internationally contagious. General Fanshaw, commander of the British 48th division, had adopted an up-to-date system of elastic defense. This enabled him to absorb an Austrian penetration of his line and recover lost ground by counterattacks the following day. However, even this brief enemy incursion was enough to get him fired. General Diaz, throughout the summer, still refused to move despite the fury of the Allied generalissimo, General Foch whose authority, however, only extended somewhat tenuously to Italy. Like all Allied generals, Diaz expected the war to last until the following year. However, the tide in France had now turned and with the relentless Allied advance and the swelling American contribution, it became a safe bet to go on the offensive. Also the Prime Minister, Orlando, wanted Italy to get as much lost territory under her belt before the war ended. The result was the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, an attack launched across the Piave in late October and spearheaded by the two remaining British divisions. After fiercely resisting for two days, the Austrians threw in the towel and went home refusing to defend an empire that was already breaking up behind them as nationalist aspirations coalesced. An Armistice was signed at the Villa Giusti on November 4. Though the victory contained elements of a walk over, it could at least be seen as a decisive defeat, unlike on the Western Front where the German line never broke, fostering the legend exploited by Hitler of an undefeated army stabbed in the back by politicians and revolutionaries.

It was the Italian prime minister in 1914, Antonio Salandra, who coined the unfortunate phrase, "sacro egoismo" to justify Italy's neutrality. Most nations operate on this principle a good deal of the time both in war and peace, but at the time it compared unfavorable with the higher ideals of France, who fought to expel the enemy from her territory or Britain, who fought to defend the integrity of Belgium. At the Versailles peace conference, Italy continued to appear more opportunistic than idealistic. As well as the Trentino up to the Brenner and the city of Trieste, she also claimed the German-speaking south Tyrol, and chunks of the Balkans and East Africa. In doing so, she was only asking the Allies to fulfill the obligations of the Treaty of London, but the world had changed. The 14 points of President Wilson now dominated the agenda and Italian demands for non-Italian speaking territory violated Wilson's principles of national self-determination, especially in the Balkans. Italian national pride, vociferously expressed, encouraged Orlando to abandon the conference when Italian demands were not fully met. However, he had to return with his tail between his legs in order to ratify what he really wanted; the Trentino and Trieste. |

|

However, the Italians still felt cheated and Orlando had to resign. The situation was then exacerbated by D' Annunzio's seizure of Fiume, which the government could not prevent. This both added to Italy's internal sense of a mutilated victory and her external reputation as greedy and opportunistic. In fact, as I said earlier, territorial ambition is hardly an unusual motive for fighting, and Britain and France had no hesitation in exploiting their victory for imperialist gain, especially in Africa and the Middle East. The consequences are still with us. The real cause of the bad reputation of Italy's victory has been as a prelude to Fascism. There is no question that the militarization of Italy in the Great War, like the militarization of Germany, established a precedent of national self-aggrandizement as a solution to national disunity, and the image of Italian Arditi (crack assault units) degenerating into fascist thugs stays in the mind. However, if World War II is anything to go by, the defeat of Germany was surely a good idea, and for Italy's part in it, one should be grateful. The German army was among the finest ever put in the field, not a product of citizen conscripts, but of a disciplined nation in arms, and any alliance setting out to beat it needed all the help they could get. The centennial of World War I will be upon us within a decade. The Western Front currently attracts a quarter of a million visitors a year and even a remote battlefield like Gallipoli when the Anzacs were blooded in 1915, is visited by Australians of all ages, who rightfully see it as a milestone in defining their nationhood. In Italy nationhood has still to mature and is retarded by an unusually pervasive distrust of the political class perceived as putting their own interests first. Admittedly, everyone tends to complain about Italy out of habit, without really meaning it and life is generally good there. However, one factor does delay the solution of problems quite seriously. As in Latin America, when times are good, tutto va liscio, but when things go badly, every interest group retreats into itself and paddles its own canoe. A dash of patriotism may be the answer. If the role of Italy and of the Savoy family in the Great War can achieve greater recognition as a job well done, this might contribute to a greater sense of national pride, even in today's globalized technocratic world, Hopefully through a more positive attitude to Italy in the Great War, patriotic gore can rekindle a brighter patriotic core in the Italy of today.

|

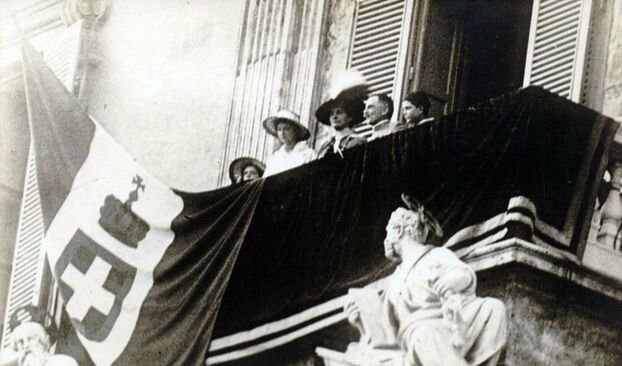

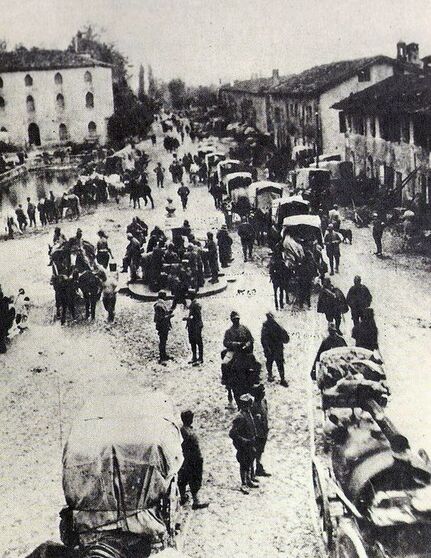

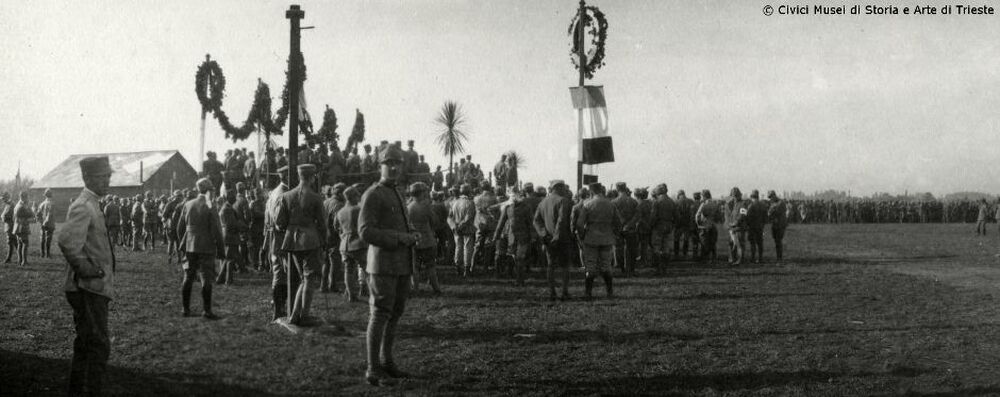

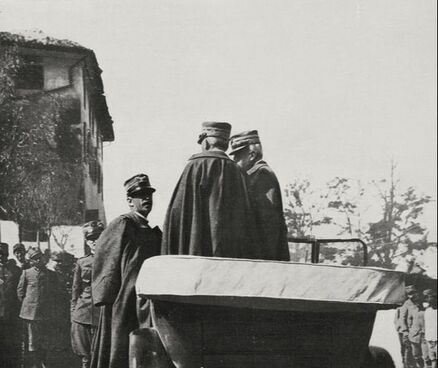

Parade along the Dock of Trieste, after Annexation to the Kingdom of Italy.

King of Italy Victor Emmanuel III and the Italian general chief of staff Armando Diaz, after descending from the destroyer Audace, take place on the cars opening the parade in the harbour of Trieste, occupied by the troops of the Kingdom of Italy on November 3, at the end of the War World I; in the close-up, a marching band. Trieste (Italy), November 10, 1918.

|